TADA Tomomitsu Solo Exhibition, “Do these soulless, vacant puppets feel any distance or shame living in a world where they blindly accept information from corrupt, hollow shells of humans and, without even thinking for themselves, naively cause each other pain…☆ 卍”

April 28 — June 17, 2018

TADA Tomomitsu

Being present (Rondo), 2018

Indian ink, pearl

For the Proof of the Inviolability of Spiritual Freedom: Drawing and Exhibition of TADA Tomomitsu

HOSAKA Kenjiro, Curator of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

This exhibition is full of positive anger.

First of all, it is shown clearly in the expression of the title. Let me quote the title which is long enough to say that it is odd.

“Do these soulless, vacant puppets feel any disgrace or shame living in a world where they blindly accept information from corrupt, hollow shells of humans and, without even thinking for themselves, naively cause each other pain…✩ 卍 “ (Originally there is a face of an animal like a bear between the asterisk and the 卍 fylfot.)

The title has 125 letters in Japanese. This number of letters and characters reminds us of Twitter where one tweet is limited to 140 letters and characters in the case of Japanese. Considering that he dares to write with such a word number for criticism against SNS, it possibly implies that “soulless puppets” refer to the so-called online neo-nationalists. Even if there is no such implication in the number of letters and characters, it is possible to read this interrogative sentence as a criticism against those who utter hate speech saying, “Don’t you know that your existence itself is a shame in the existential meaning?”

Anyway there is no doubt that he is angry about the current situation, but he is never overwhelmed by anger. Even if the intensity of anger is strong, he knows how to convert it to something creative and aesthetic. That technique is amply demonstrated in the composition of his exhibition.

This exhibition consists of four parts. If I say the conclusion first, the third room plays the role of a divide in asserting the inviolability while each of the second and fourth room shows the possibility of what can be conceived from the fundamental human rights. (Beware that it is a possibility not an option.) Or you can say that he is trying to prove the preciousness of spiritual freedom by making works in the second and fourth rooms.

This proof will be a considerably risky bet. In the first place, if you are an artist, you should be able to claim freedom in any work. And yet Tada challenged a direct confrontation. He actually brought out the concept of “spiritual freedom,” and succeeded in its “proof.” How did he do that? I will examine his proof method more closely below.

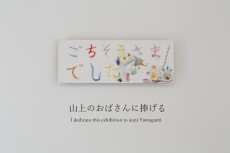

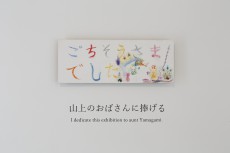

The first room functions as an introduction, so to speak. A long title characterizing this exhibition, a foreword by the organizer, and two small pieces are hung in such a small room that it is difficult to call it an exhibition room.

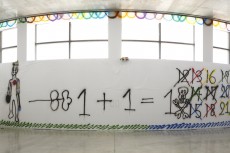

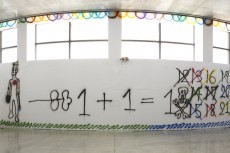

The second room is long, tall and narrow following a curve. A freehand drawing is drawn on the whole wall on the right hand side just inside the entrance. I said that it is “a hand drawing,” but actually the drawing stroke of the arc is so large that we can hardly believe that it was produced by the physical size of a human. I was interested in who did it or how it was drawn. With the drawing in front of us, which is liberated from the human size, we come to enjoy liberation of our spirit with a subtle feeling of awe. (In fact, as it seems to have adopted the watering system used for gardening, it should exceed the limits of human hands.)

Several numbers are drawn on the wall on the opposite side. The most eye-catching among them is a formula, 1 + 1 = 1. This formula of mysticism (that could be something secretly telling the world’s truth), which was also written on the wall in “Nostalgia,” a 1983 film by Andrei Tarkovsky, resonates amazingly with an over-scale drawing placed face-to-face.

How about the short wall sandwiched between the two walls drawing a curve? There is a framed drawing on the side close to the entrance. There is only one freehand straight line drawn almost horizontally. Regarding what this line means, the following passage in “Lines” by Tim Ingold provides useful insight.

“…The relentlessly dichotomizing dialectic of modern thought has, at one time or another, associated straightness with mind as against matter, with rational thought as against sensory perception, with intellect as against intuition, with science as against traditional knowledge, with male as against female, with civilization as against primitives, and—on the most general level—with culture as against nature.” Ingold called such a line “an icon of modernity.” This short straight line that is the only framed item in this exhibition is carefully displayed as “an icon of modernity” in its earliest stage based on the interest of natural history, so to speak.

On another short wall, there are cat’s mew drawn both in katakana and hiragana letters. Writing or recording voice in letters is deeply involved in “modernization” as Walter J. Ong explained, for example. It is obvious that Tada is trying to study drawings in view of both pre- and post- modernization.

The third room is enclosed with black curtains. Close to the ceiling in the corner opposite the entrance are blue neon tubes that read “spiritual freedom” in Japanese. If they were in kanji characters, there would be a lot of straight lines, but since they are written in hiragana, they consist of curved lines. As a result, they look like a drawing or graffiti. In other words, they look like words in their beginning. Even for those visitors who cannot read Japanese, they could sense that quality due to the curves or because it looks like a drawing. At the same time, the blue light makes the words or the concept look almost sublime. The physical inviolability that it is in an unreachable high place enhances its sublimity.

The forth room is much more compact in the height of the ceiling and area, compared to what we have seen so far. It looks even ordinary. The light in the room, however, is dark like twilight, so we do not feel that it is perfectly ordinary. It is in between the ordinary and the extraordinary, as one might say.

Installed in the center of the room is a large oval board as if floating. There are a number of things on it that look like origami or ceramics. They look either finished or in the process. On the wall are three pieces of ceramic ware that look like a bear’s face. They look like masks, but then it is strange that they are made of ceramic, and their size is small. There are no openings for the eyes. The arrangements of the whole room, however, make things look related to folklore or human activities, that is, mask-like things.

There is a room where inviolability as well as sublimity of “spiritual freedom” can be experienced, and the room prior to it was an over-scaled room that transcends rationality. For some reason, it looks plain. A room following it seems to have been incidentally born in between the ordinary and the extraordinary, and is filled with things that are totally familiar to human hands. It is obvious that the third room is considered to be the base point, that is, a divide, and the contrast between the second and the forth room is emphasized. And it is also clear that the both rooms are related to the act of expression or spiritual freedom of expression. Tada has presented two possibilities that could be conceived from “spiritual freedom.”

If I would raise a question about the exhibition here, it is possible to critically claim that he should present an alternative that people would frown at, like pornography.

Tada, however, did not do that. Why? Probably because the destination of his interest is not to question where the limit of spiritual freedom is, but to think about the reason why such a concept of spiritual freedom is conceived in the first place. That is why he tried to probe into the possibilities of drawing based on subtle physical ecstasy instead of pornography. One of the finest things this time is that Tada tried to think about it, not confined to the issue of lines literally, but including expressions closely related to hands as being presented in the fourth room, as if Ingold was introducing various examples. And another good thing is that he made it possible to experience it in the exhibition space. Tada has challenged to prove, not through words, the inviolability of fundamental human rights in today’s Japan, and wonderfully succeeded in doing it. I’d like to express my sincere respect to the artist.

1) Tada says that he did not know of this scene in the film. Rather, during his production of this exhibition, he thought of fragments of the images in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. (e-mail to the writer, July 10, 2018)

2) Tim Ingold, Lines, A Brief History (Oxford: Routledge, 2007), 152.

3) Ingold, Lines, 167.

4) Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, Walter J. Ong, trans. Naofumi Sakurai et al. (Tokyo: Fujiwara Shoten, 1991).

Freedom, 2016

acrylic on paper, 105×150mm

Thank you for the meal, 2010

watercolor pencil on wood, 170×445mm

Being present, 2018

pastel on paper, 248×338mm

Being present (Rondo), 2018

Indian ink, pearl

Being present (Rondo), 2018

Indian ink, pearl

Being present (Rondo), 2018

Indian ink, pearl

Freedom of Spirit, 2018

neon tube, board, size variable

Untitled, 2018

mixed media, size variable

Untitled, 2018

mixed media, size variable

多田友充展「性根の腐った誠実さのかけらもない人間どもの流す情報を、ただただ鵜呑みにして自らの頭で考えることもせず無邪気に人に暴力を振るう、たましいのない空っぽの操り人形どもは、果たしてこの世界に存在することに恥ずかしさや情けなさを感じることはあるのだろうか☆ 卍」

2018年4月28日(土)-6月17日(日)10:00-18:00 会期中無休/無料

多田 友充

TADA Tomomitsu

精神の自由の不可侵性の証明に向けて:多田友充のドローイングと展覧会

保坂 健二朗(東京国立近代美術館主任研究員)

この展覧会は、明るい怒りに満たされている。

それはまずタイトルの表現方法に明らかだ。異様だとも言えるほどに長いそれを、ここに引用しておこう。「性根の腐った誠実さのかけらもない人間どもの流す情報を、ただただ鵜呑みにして自らの頭で考えることもせず無邪気に人に暴力を振るう、たましいのない空っぽの操り人形どもは、果たしてこの世界に存在することに恥ずかしさや情けなさを感じることはあるのだろうか☆ 卍」(本来、星印と万字紋との間には、熊のような動物の顔がある)。

タイトルの字数は125文字。一回あたりの投稿が日本語の場合は140文字となっているTwitterを思い出させる字数だ。SNSに対する批判のためにあえてそのような字数で書かれたのだと考えれば、「たましいのない操り人形ども」というのはいわゆるネトウヨのことを意味している可能性がある。文字数にそういう含意がなかったとしても、この疑問文を、たとえばヘイトスピーチをする人たちに対して「あんたらそもそも自分の存在そのものの、実存主義的な意味での情けなさを知らないのか」という批判として読むことは充分に可能だ。

なんにせよ、多田が現在の状況に対して怒っているのは間違いない。しかし彼は怒りに絡め取られることは決してない。たとえ怒りの強度が強かったとしても、多田はそれを、創造的かつ感性的なものに転化する術を知っている。そしてその術は、展覧会の構成に対していかんなく発揮されている。

この展覧会は、四つのパートから構成されていた。結論を先に言ってしまえば、「精神の自由」の不可侵性を主張する第三の部屋を分水嶺にして、第二の部屋と第四の部屋それぞれが、その基本的人権からうまれえるものの可能性を示している(あくまでも可能性であり選択肢ではないことに注意しよう)。あるいはこうも言える。多田は、精神的自由の尊さを、第二の部屋と第四の部屋の作品をつくることによって証明しようとしているのだと。

この証明は、相当リスキーな賭けになる。そもそもアーティストであれば、いかなる作品においても自由権を主張できるはずなのだ。それなのに多田はここで真っ向勝負を挑んだ。「精神の自由」なる概念を実際に持ちだした。そして見事に「証明」に成功した。それはどのようにしてだったか。以下では彼の証明方法を今少し詳しく見ていく。

第一の部屋はいわばイントロダクションとして機能している。この展覧会を特徴づける長いタイトルと主催者挨拶と小品二点とが、展示室ともつかない小さな部屋に掛けられている。

第二はカーヴを描く、細長く高い部屋で、入口入って右手の壁には、フリーハンドのドローイングが壁全体に描かれている。今「ハンド」とは言ったものの、円弧を描くドローイングのストロークはあまりにも大きく、それは、人間の身体のサイズからはおよそ生み出しえないほどである。一体誰の手によって、あるいはどうやって描かれたのかと気になる。人間の身体のサイズからは自由なドローイングを前にして、私たちは、少しの畏れとともに、精神の解放を味わうことになる(実際には園芸で使う水まきの仕組みを応用したらしく、なるほど「手」の限界を超えるはずである)。

その反対側の壁には数字がいくつも描かれている。なかでも眼をひくのは1+1=1という数式だ。アンドレイ・タルコフスキーの映画「ノスタルジア」(1983年)でも壁にかかれていたこの神秘主義的な(あるいは世界の真理をこっそりと伝えるかのような)数式は、その対面にあるオーバースケールのドローイングと見事に共鳴する[1]。

カーブを描くふたつの壁に挟まれた短手の壁はどうか。入口に近い側には額装された一点のドローイングがある。描かれているのは、ほぼ水平に引かれたフリーハンドの直線が一本のみ。この直線がなにを意味するかについては、ティム・インゴルドの『ラインズ』に見える次の一節が参考になる。「近代的思考の徹底的な二項対立図式のなかで、直線は、物質に対向する精神に、感覚知覚に対抗する理性的思考に、本能に対する知性に、伝統的な知恵に対抗する科学に、女性原理に対抗する男性原理に、原始性に対抗する文明に、そして——もっと一般的なレベルにおいて——自然に対抗する文化に、しばしば結びつけられてきた」[2]。インゴルドはそんな直線を、「近代性のイコン」[3]とも呼んでいる。本展の中で唯一額装されたこの短い直線は、美術作品というよりは、むしろ、「近代性のイコン」の最初期のものとして、いわば博物的な関心に基づいて、大切に展示されている。

もう一つの短手の壁には猫の鳴き声が、片仮名(ニャーニャー)と平仮名(にゃーにゃー)とで描かれている。声を文字で書く=記録するというのもまた、たとえばウォルター・J・オングの研究が明らかにしたように「近代化」に深く関わる。多田は明らかに、近代化の前と後、双方を視野に入れてドローイングを考えようとしている[4]。

第三の部屋は、黒いカーテンに囲まれている。入口の反対側の角の天井近くには青のネオン管が掲げられていて、それは「せいしんのじゆう」と書いている。漢字(精神の自由)であれば直線が多くなるが、平仮名ゆえに曲線が基調となっている。その結果、ドローイング的に、あるいは落書き的に見える。初発的な言葉に見えると言い換えてもよい——たとえ日本語が読めない訪問者だったとしても、その曲線性ゆえに、あるいはドローイングのように見えるがゆえに、初発性は伝わることだろう。その一方で、青い光がその言葉を、あるいはその概念を、崇高にすら見せる。手が届くはずもない高いところにあるという物理的な不可侵性が、その崇高性を強化する。

第四の部屋は、これまでに比べると、天井高も面積もずっとコンパクトだ。日常的ですらある。ただし室内の明かりがまるで薄暮のようになっているから、完全な日常とも感じられない。いわば、日常と非日常の間のような空間である。

そんな部屋の中央に大きな楕円形の板が浮かぶように設置されていて、その上には折り紙のようなものや陶器のようなものがいくつも置かれている。完成品のようにも制作途中のようにも見える。壁には三つ、熊の顔面を象ったような陶器が掛けられている。マスクのようにも見えるが、だとすれば陶器というのはおかしいし、サイズも小さい。眼のための穴もあいていない。けれども、この部屋の全体の設えが、それらを民俗と関係あるものに、人の営みと関係あるものに、つまりはマスク的なものに見せる。

「精神の自由」の不可侵性を崇高性とともに体感させる部屋がある。その前が、合理を超越したオーバースケールの部屋だが、なぜかあっけらかんとしている。その後が日常と非日常の間にふとうまれたような、どこまでも人の手と親しくあるものに満たされた部屋だ。第三の部屋を基点=分水嶺にして、第二の部屋と第四の部屋の対照性が強調されているのは明らかである。そして、そのどちらの部屋も、表現という行為に、あるいは表現という精神の自由に関連していることも明らかである。「精神の自由」から生まれうるものの可能性をふたつ、多田は提示したわけだ。

もちろんここで、もし問題提起をするのであれば、もっと別の、たとえばポルノグラフィのような、ともすれば人が眉をひそめるような可能性を示すべきだという批判も可能だろう。

だが多田はそれをしなかった。なぜか。おそらくそれは、彼の関心の向かう先が、精神の自由の限界がどこにあるかを問うことではなく、精神の自由という概念が生まれ出てくるそもそもの理由を考えようとすることにあるからだ。だから彼は、ポルノグラフィなんかではなく、身体的なささやかな快楽に基づくドローイングの可能性を問おうとした。今回の白眉のひとつは、多田がそれを、リテラルに線の問題だけではなく、まるでインゴルドが様々な事例を紹介するように、第四の部屋に現れているような、手と密接に関連する表現も含めて考えようとしたことにあるだろう。そしてもうひとつは、彼がそれを、展覧会という空間体験において感得できるようにしたことである。基本的人権の不可侵性を、今の日本で、言葉でなく証明することに挑戦し、見事に成功したこのアーティストに、私は心からの敬意を、今ここで捧げたい。

[1] 多田はこの映画のこのシーンを知らなかったそうで、むしろ本展を制作中には、イングマール・ベルイマンの「第七の封印」のイメージの断片を思い浮かべていたという。 筆者宛の電子メール(二〇一八年七月一〇日付)

[2] ティム・インゴルド『ラインズ 線の文化史』工藤晋訳、左右社、二〇一四年、二三四頁。

[3] 同書、二五四頁。

[4] ウォルター・J・オング『声の文化と文字の文化』桜井直文他訳、藤原書店、一九九一年

《無題》2018年

ミクストメディア、サイズ可変