Courage in Transience

July 27 (Sat) – September 8 (Sun), 2019, 10:00-18:00, admission free

Carlos NUNES

“Play” as the essence of human activities

KEINO Yuka

“where am I, who am I, where am I going”

Carlos NUNES presented these questions about his own existence for a group of works he made in Aomori. He is not heavy-footed, however. He keeps on moving his hands while he takes on a sense of floating and tries to find answers for the grand questions on his own.

He resigned a designer job to work as an artist, and in his installation works, he often expresses the consequences of things and matters by combining familiar materials including daily goods and fire with the phenomena. In recent years, he films the phenomenon itself to incorporate what is difficult to visualize such as light, time, nature and energy generated by people. His works seem to explore the relationship between physical laws of the universe and life beyond the “play” of things and words that are brought about by his works and titles.

Johan Huizinga, a pioneer who studied human “play,” understood that play was the essence of human activities and the source of culture. According to Huizinga, “Summing up the formal characteristics of play we might call it a free activity standing quite consciously outside ‘ordinary’ life as being ‘not serious’, but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. It is an activity connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained by it. It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner. It promotes the formation of social groupings which tend to surround themselves with secrecy and to stress their difference from the common world by disguise or other means.” (*1) Bearing this in mind, I would like to think about Nunes’s production here.

Due to a visa problem, his stay was unfortunately shorter than scheduled. Before he departed for Japan, he had sent his work “light hole” (2017) there, which was made with silk paper(*2) that was relatively easy to buy in Brazil and the material familiar to him. He planned to make it the starting point of his residency production of work-in-progress after he arrived.

At first glance, the paper stuck on the wall seems to be illuminated by light, but looked at closely, the lamp is off, and you can see that the paper itself has been crafted as if it were illuminated by light. In fact, the color has faded as a result that the artist kept shedding light on the paper for months.

With such simple ingenuity, an eclipse-like scene is lightly created by continuing simple experiments. As the work is presented with its poetic title, the viewer is urged to stop and observe it closely.

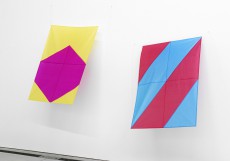

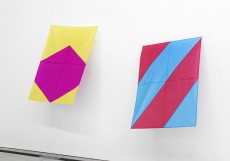

Using the same silk paper, he made new work “pipa”. Kite-flying is popular in Brazil as it is in Japan. Over there, it has more of a competitive element; if you hook the opponent’s thread and cut it, you win.

Nunes cut as many colorful pieces of paper as he could to make a kite, and by reconstructing them, he produced various geometric patterns. He then examined how the kite should fly in the exhibition space, and eventually made it look like how Kasimir Malevich presented suprematism painting as a dynamic movement having the fourth-dimension in mind at “The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0. 10 (Zero-Ten)” held in Petrograd (present St. Petersburg) in Russia in 1915. (*3)

In terms of suprematism in which abstraction was explored and the relationship with the real world was eliminated, his idea was inspired by familiar things, yet you can see his attitude trying to escape from ordinary world.

His works in which the element of “play” is most noticeable are “meteoro (meteorite)” (2017) and “fototaxia (phototaxis)” (2017/2019), both of which are video works. The artist set fire to fireworks on the rocky ground at dusk. He video-recorded it in slow motion, and it shows how the sparks slowly intensify and weaken towards the end. It seems to be a metaphor for the life of an organism. The reproduction of “meteoro” was attempted in Japan where it is easier to buy fireworks than in Brazil. In order to film it in a short time before dark, he looked for a deserted place and eagerly ignited fireworks. It looked as if a boy was enthusiastic about an experiment banned by parents at his secret base.

“fototaxia (phototaxis)” finally exhibited was inspired by steel wool that sparks when lit, and he made a rotating machine using the surrounding things such as a chair and an electric fan and recorded how the sparks rotated. Like phototactic insects, the work seems to touch upon the instinctive nature of creatures going for external stimuli including “play.”

His “sculpture with aomori air” is also a work characterized by the element of “play” in which a familiar garbage bag is worked on to be an “objet d’art” by putting air into it. The performance by the artist was actually given and the audience could experience it inside the gallery. They were immersed in this simple action to create a mysterious sense of unity.

As he introduced in his artist talk(*4) , he would unmistakably join a series of artists who had explored how things and sculptures could be based on “play” like Calder who made mobile sculpture that looked like playing with air, Fischli & Weiss, Erwin Wurm, and Roman Signer.

By the way, Paul Gauguin painted “D'où venons-nous? Que sommes-nous? Où allons-nous? (Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?)” (1897—1898), inspired by tropical Tahiti and questioning the existence of humans.

In Brazil, a cultural movement called “Tropicália” happened in the 1960s as people sought after unique hybrid tropical culture of many immigrants. Hélio Oiticica, the major artist of this movement incorporated interactions between artworks and the viewer while he was influenced by abstract expressions such as concrete art and De stijl.

During the time of our lives, anyone would ask the question of self-existence. Having understood the late painter’s question of the Western civilization and his view of integrating contradictory images and having followed the flow of contemporary art in Brazil since the 1960s, which is minimal yet energetic, Carlos Nunes gives a simple guideline to the big question of self-existence, that is, “44cm”. What is felt at heart is thought over in the head and turns into an expression. The length from Nunes’s heart to the top of the head is exactly 44cm. Oiticica once said, “To live is art itself.”

(*1) Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens, A Study of the Play-element in Culture (London, Boston and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1949), 13. Yale School of Art, http://art.yale.edu/file_comuns/0000/1474/homo_ludens_johan_huizinga_routledge_1949_.pdf

(*2) Silk paper is very thin like tissue paper, and it is similar to “hana-gami,” a material used in layers for artificial flower decorations. It is available in Japan, but it is more reasonable and comes in many different colors in Brazil.

(*3) See photo.

(*4) Artist talk was held on August 10, 2019 (Sat.) under the title, Carlos Nunes “Oncotô (where am I ).”

(tranlated by NISHIZAWA Miki)

Kasimir Malewitsch, Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10, 1915

44cm

Drawing on the wall

2019

Sculpture with Aomori air

performance

2019

44cm

Drawing on the wall

2019

above all photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

はかなさへの果敢さ

2019年7月27日(土)-9月8日(日)10:00 18:00、会期中無休、無料

air2019-3ja

カルロス・ヌネス

Carlos NUNES

人間活動の本質としての「遊び」

慶野 結香

「私はどこにいるのか 私は誰か 私はどこに行くのか」

カルロス・ヌネスは、青森で制作した作品群に、この自らの存在に対する問いを掲出した。ただ、その足取りは決して重くない。彼は一種の浮遊感をまといながら、手を動かし続けることで、この大きな問いに自分なりの答えを見つけ出そうとしている。

デザイナーの職を辞し、アーティストとしての活動をはじめた彼は、日用品と火など身近な素材と現象を組み合わせ、そこから生じた物事の結果について、インスタレーションとして表すことの多いアーティストである。近年では、その現象自体を映像で捉えることによって、光や時間、自然や人間が生み出すエネルギーなど、なかなか可視化することが難しい力を作品の中へ取り入れている。まるでそれは、作品とその名前がもたらす、物と言葉による「遊び」の域を超えて宇宙の物理法則と生命の関係を探求するかのようだ。

人間の「遊び」について考察した第一人者であるヨハン・ホイジンガは、遊戯が人間活動の本質であり、文化を生み出す根源だと捉えた上で、「遊びは自由な行為であり、『ほんとのことではない』としてありきたりの生活の埒外にあると考えられる。にもかかわらず、それは遊ぶ人を完全にとりこにするが、だからと言って何か物質的利益と結びつくわけでは全くなく、また他面、何かの効用を織り込まれているのでもない。それは自ら進んで限定した時間と空間の中で遂行され、一定の規則に従って秩序正しく進行し、しかも共同体的規範を作り出す。それは自らを好んで秘密で取り囲み、あるいは仮装をもってありきたりの世界とは別のものであることを強調する。(*1)」とした。このことを念頭に置きながら、今回のヌネスの制作について考えてみたい。

ビザの関係で、残念ながら当初の予定より期間が短くなった青森での滞在制作であったが、到着後にワークインプログレスとして滞在制作を行う際の起点として、ヌネスは扱い慣れた素材、ブラジルで比較的入手しやすいシルクペーパー を用いた《light hole》(2017年)を自身より先に日本へ送った。

一見すると、ライトによって壁に貼られた紙が照らされているようだが、よく見るとランプは消えており、シルクペーパー自体に光が当てられているかのように見える細工が施されているのがわかる。しかしこれは何ヶ月もかけて、作家が実際にペーパーにライトを当て続けた結果として色が褪せているのだ。

簡単な創意工夫から、まるで日食のような情景を軽やかに、しかし地味な実験の継続から生み出す。それが詩的なタイトルと共に呈示されることで、作品を見る者の足を止め、じっくりとものを観察することを促す。

同じくシルクペーパーを使った作品として、新作《pipa(凧)》も制作した。日本と同じくブラジルでも凧揚げはポピュラーな遊びであり、かの地では糸を引っ掛け、相手の糸を切ったら勝ちという競技的側面も強い。

ヌネスは、凧一枚ができる枚数の色とりどりの紙(*2)をまとめて切り、再構成することで、実に様々な幾何学的模様を生み出した。そしていかに凧が展示空間の中で浮遊すべきか吊り方を検討し、最終的には1915年にロシアのペトログラード(現サンクト・ペテルブルグ)で行われた「最後の未来派絵画展0. 10(*3)」でカジミール・マレーヴィチがシュプレマティズムの絵画を、四次元が意識されたダイナミックな運動としてプレゼンテーションしたかのような作りとなった。抽象性を突き詰め、現実世界の関係を排除したシュプレマティズムから考えれば、身近なものから着想を得つつも、ありきたりな世界から逃れ出ようとする姿勢が窺える。

「遊び」の要素が最も顕著な作品としては、共に映像作品である《meteoro(隕石)》(2017年)、《fototaxia(走光性)》(2017/2019年)が挙げられる。夕暮れ時の岩場で、噴き出し花火に着火する作家本人。その様子をスローモーションで記録することで、火花がゆっくりと強くなり、やがて終わりに向かって弱まっていく様が、まるで一生命体の生涯のメタファーであるかのようにも見えてくる。この《meteoro》に関しては、ブラジルよりも花火が購入しやすい日本でも再制作が試みられた。暗くなる前の短時間で撮影するため、人気のない場所を探し、必死に花火へ点火する姿は、まるで少年が秘密基地で親からは禁止されている実験に熱中するかのようだった。

最終的に展示された《fototaxia》は、スチールウールに火を点けると火花が散ることに着目し、椅子や扇風機の機構など周囲にあるものを用いて回転機械を作り、火花を回す一連の様子を撮影したものである。虫が光に向かっていく「走光性」のように、「遊び」を含む外的な刺激に向かっていってしまう、生物の本能的な性質にまで言及するかのようだ。

《青森の空気による彫刻》も、身近なゴミ袋に細工を施し、空気を入れてオブジェ化するという「遊び」の要素が強い作品である。実際に作家によるパフォーマンスも行われ、ギャラリー内では鑑賞者も体験することができた。単純な動作に、我を忘れて没入する様子は、不思議な一体感を醸し出していた。

本人もトーク(*4)で紹介していたように、空気と戯れるかのようなモビール彫刻を作ったカルダーにはじまり、フィッシュリ&ヴァイス、エルヴィン・ヴルム、ロマン・シグネールなど、「遊び」をもとに物や彫刻のあり方を探求しているアーティストたちの系譜にヌネスも間違いなく連なるだろう。

ところで、ポール・ゴーガンも《我々はどこから来たのか 我々は何者か 我々はどこへ行くのか》(1897-1898年)を描き、熱帯のタヒチからインスピレーションを得て、人間の存在について問うている。

ブラジルでは、1960年代に多くの移民から成るハイブリッドな熱帯独自の文化を模索する「トロピカリア」という芸術運動が起こった。このムーブメントを代表するエリオ・オイチシカは、コンクリート・アートやデ・ステイルといった抽象表現の影響も受けつつ、作品と鑑賞者の相互作用をも取り入れた。

生かされている時間のなかで、誰もが抱くであろう自己の存在への問い。西洋文明に疑問を投げかけ、相反するイメージを統合した画家のまなざしも、60年代から続くブラジルという国の、ミニマルでありながら生命力を感じさせる現代美術の流れも汲んだ上で、カルロス・ヌネスはこの大きな問いに、シンプルな指標を与える。それは《44cm》。心で感じられたことが、頭で考えられて、表現となる。ヌネスの心臓から脳天までは、ちょうど44cmだったのだ。オイチシカも言っている、「生きることはアートそのものだ」と。

(*1)ヨハン・ホイジンガ、里見元一郎訳『ホモ・ルーデンス』河出書房新社、1974年、p. 31

(*2)ティッシュのような薄い紙で、日本では重ねて装飾用の花を形作る「花紙」の素材に類似している。日本でも入手可能だが、ブラジルではより安価に多くの色の紙を購入可能。

(*3)写真参照

(*4)2019年8月10日(土)に実施。カルロス・ヌネス「Oncotô(where am I ?)」

《light hole(ライトホール)》

黒色シルクペーパー、消えたランプ

2017

以上 撮影:山本糾

pipa(凧)

シルクペーパー、糸

2019

以上 撮影:カルロス・ヌネス

meteoro(隕石)

映像6分31秒

2019

《fototaxia(走光性)》

映像3分41秒

2017 / 2019

《青森の空気による彫刻》

パフォーマンス

2019

44cm

壁にドローイング

2019

以上 撮影:山本糾