Courage in Transience

July 27 (Sat) – September 8 (Sun), 2019, 10:00-18:00, admission free

MIHARA Soichiro

Natural Observation, Formation of Nature

-Artifact 1. Site

An Open Laboratory of Art

MURAKAMI Aya

MIHARA Soichiro has, throughout his career, exhibited works that make use of autonomous systems to generate given phenomena. His interests lie in functions, phenomena, and the environments that surround an artwork. For this exhibition, Mihara chose as his laboratory an observation site that encompassed the natural environment and a modern-day information environment in his work Natural Observation, Formation of Nature. The work has many layers that, in its entirety, revealed inconsistencies and contradictions in our social systems, from the selection of materials to conflicting situations during the production.

Natural Observation, Formation of Nature consists of five parts in four locations. Each location—the forest, the gallery space, and the ACAC Water Terrace—was connected online to receive, react to, and share environmental information with the others.

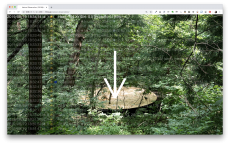

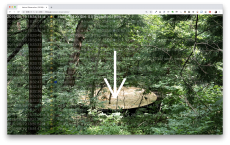

The audience is first prompted to visit Mihara’s installation Site. From a paved walkway, visitors travel down a small trail into the forest and approach a steep set of stairs. As they descend into the woods, they hear the rustling of leaves and the chirping of birds in the summer heat. Splashes and gurgles inform the visitor of a nearby stream as they follow the meandering path through dense vegetation over a wooden boardwalk that takes them deeper and deeper into the forest. The visitor crosses a bridge and hears the soggy sounds of the wetland at their feet as they continue their journey until the view opens to reveal a large, circular platform built of plain wood.

After removing their shoes, the visitor ascends the platform to be greeted by the smooth texture and light scent of hiba cypress. Directly in front of them stands a water basin made to resemble a campfire in between two mulberry trees from which hang two red tassels, which recasts the space as someplace sacred. Occasionally, water is pumped into the water basin from a tube, forming a chorus with the wind and the stream that flows to the right of Site, just past the mulberry trees. Two polygonal umbrella-like objects hang from the trees, one made of plain wood and another painted vermillion just off of the left tree trunk. The platform’s wooden planks are cut radially—their point of convergence outside of the platform—and are oriented south, pointing in the direction of the gallery.

Visitors encounter A balloon that’s being observed floating midair in the center of the gallery. A device beneath the balloon flashes green and purple lights while two yellow propellers rotate at irregular intervals with the faint, high-pitched whir of a motor. Occasionally, mist is dispensed from the mouth of a suspended bottle, and the scent of hiba spreads throughout the gallery. Directly below the balloon is a mound of soil1, made from compost, that represents the earth and is reminiscent of the hydrologic cycle.

Isolated Island installed on the ACAC Water Terrace as if staring at A balloon that’s being observed in Gallery B. Just below the eaves sits a hand cymbal used in Aomori’s Nebuta festival, which is played by falling raindrops. On a quiet day, its metallic song rings out at a distance, far and out of sight of the pond.

Though not visible from Site, traces of a small hokora shrine remain at the top of a steep slope to the east. The small structure was once a part of Towada Shrine, located near Lake Towada and dedicated to the god of water. Mihara even remarked that while working with the muddy soil, he felt as if he was making an altar of sorts.2 Just as a shrine acts as a place to draw attention to “the other,” visitors will stand here in the forest, their sensitivities heightened as they look out on an overwhelming display of nature. However, this work is not meant to create a sensory and primitive dialogue with the other. It is a place to confront the environment in its entirety, including both the natural environment and the man-made objects and structures.

Site and A balloon that’s being observed both acquired local data and communicated it in real-time over a 3G internet connection using antennas located on each, and the continuous transfer of measurement data triggered actions on both devices. Site is equipped with environmental sensors that capture temperature, humidity, light, and wind as well as a PIR sensor that senses the presence of warm-blooded animals. Of these, only the PIR sensor was incorporated into A balloon that’s being observed inside the gallery, where it captured the presence of anything with body heat.

Whenever someone visits the gallery space, water is pumped from the stream into the basin at Site. Whenever hiba-scented mist sprays from the bottom of A balloon that’s being observed, it indicates that the PIR sensor beneath the dark vermillion umbrella at Site has detected someone—or something—there. The continuous high-pitched whirs of propellers sound like a warning, the result of control signals that precisely reflect data from the wind, which would update every few seconds. This wind data is gathered and measured by six small microphones placed horizontally 60 degrees apart in a hexagonal pattern beneath a plain wooden umbrella structure at Site. Based on temporal differences, wind direction and velocity is calculated as extremely low-frequency sound and converted into driving data for propellers on two different axes, altering their rotational directions and speeds in real-time.

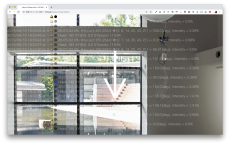

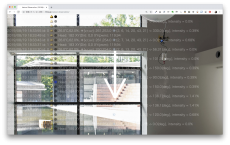

Monitoring Website published the environmental information collected from Site and A balloon that’s being observed online in real-time. The website is updated every ten seconds, a continuous and immediate display of transparency that shows exact sensitivity—quite the opposite to the experience of the human body. By showing in real-time environmental information that can be quantified and visualized—even going as far as to include signs of existence and human presence—Mihara shows us the information environment (surveillance society) in which we live and juxtaposes it with the overwhelming amount of sensory information and data within the forest.

In Natural Observation, Formation of Nature, phenomena appear to be irregular or erratic to the audience—the spray of mist, the drawing of water, the spin of a propeller. But each one is governed by causal relationships that show the audience a microcosm of the world and its many cycles and interdependencies. 100W solar panels lined the path to the Site and provided all the energy needed to power the devices. Additionally, Aomori hiba cypress was sourced for the wood used in Site and for the mist in the gallery space. The mist moistened the composted soil below, out of which a tree, whose seeds were also from Aomori, began to sprout and grow. Mihara even dyed the thread for hanging devices and sensors using pigments from the mulberry tree, whose deep, purple fruits would drop and stain the light hiba wood during the construction of the Site, much to the chagrin of Mihara and his team. Not only does Mihara’s creative system connect back to the natural environment, but it also links back to Aomori through its materials as well as to people’s everyday lives through his collaborative composting project. His work is like a miniature garden into which a sliver of the world is neatly partitioned.

Mihara had initially planned to build a compost toilet in the woods. This project would have also contrasted the time that it takes for microorganisms to return to the soil and the time it takes to dispose of and break down nuclear fuel. At the same time, it would have put into perspective the impossibility of achieving a nuclear fuel cycle. In the composting project, people tried to keep microorganisms happy and healthy in order to produce viable soil. This unnatural sight ironically overlaps with the human predicament, which is ultimately at the mercy of the physical environment. Mihara establishes his experimental laboratory in the form of an artwork in this little corner of the world. In it, he uses the causality we see unfold in the realities before our very eyes, namely the materials and different phenomena, to draw our attention to how naturally modern society embraces the irrationality—or the unreality, as he calls it—of ideas like the nuclear cycle.

Isolated Island kept its distance from the relationships of surveillance and generation. The work added a different perspective, its clear tones calling us to stop from afar. The hand cymbal could not ring out in a drizzle and was drowned out in a downpour. It seemed to speak in a language that was altogether beyond the human threshold. Trouble unexpectedly struck Mihara’s work during the last week of the exhibition, causing the propellers to spin erratically. Looking back, I think their random rotation could have been the buds of another language trying to emerge from causality. Mihara has created a laboratory that gives us a holistic look into the micro and macro environments in which we live. They allow the observer to bear witness to the dawn of a new language of the other—a language that flourishes right before our very eyes.

(*1) Collaborative production, What is eaten in Aomori will become soil in Aomori (See pp. 36-38)

(*2) From a conversation with the artist during production.

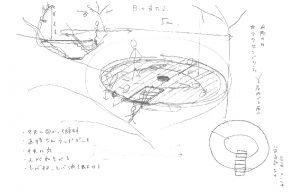

(*3) Concept sketches detailed at the end of this essay. Traces of a hole that was originally planned for the Site platform are located under the water basin.

(translated by Queen & Co.,Ltd.)

Natural Observation, Formation of Nature

-Artifact 1. Site

Natural Observation, Formation of Nature

-Artifact 5. Monitoring Website

Natural Observation, Formation of Nature

-Artifact 2. A balloon that’s being observed

Natural Observation, Formation of Nature

-Artifact 3. The Land

Natural Observation, Formation of Nature

-Artifact 4. Isolated Island

Natural Observation, Formation of Nature

Hiba tree, soil, sensor, internet, solar panel, motor, pump, thread, balloon, small cymbal

2019

Above all photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

はかなさへの果敢さ

2019年7月27日(土)-9月8日(日)10:00 18:00、会期中無休、無料

air2019-3ja

三原聡一郎

MIHARA Soichiro

自然の監視、自然の生成 -人工物1 サイト

開かれた実験場としての芸術

村上 綾

三原聡一郎は、これまでも自律したシステムによって現象を発生させていく作品を発表してきた。彼は作品で生み出される機能と生起すること、そして取り巻く環境に多くの関心を寄せる。とりわけ本展では、実験場を設えるように、実際の自然環境と現在の情報環境を内包する観測地として《自然の監視、自然の生成》を生み出した。作品の素材選びから制作中に起きる相反した状況まで、数多くのレイヤーを重ねた創作の総体によって、社会のシステムの矛盾を浮かび上がらせていく。

《自然の監視、自然の生成》は、5つの部分からなる。森の中、ギャラリー、水のテラス、インターネット上に配置され、それぞれに環境情報を受けとり、反応し、交信しあう。

鑑賞者はまず「サイト」に向かうよう促される。舗装された道から、森の中へ伸びた小道を抜け急勾配の階段へさしかかり、夏の暑さのなか葉の擦れる音や鳥の声を耳にして下って行く。水の音が水路の存在を知らせ、右手に伸びていく木道の上にアーチ状に繁茂する植物をくぐって蛇行した道を進んでいく。橋を渡り、足元の湿地から水の音が右手に移動していくのを感じながら奥に進むと、視界が開け、白木の円形の大きな構造物が現れる。

靴を脱いでその上に上がると、さらっとした感触とともにヒバの香りを感じる。正面のかがり火に似た水盆と赤い飾りのかかった二本の桑の木は、どこか祈りの場のような雰囲気をみせた。桑の木の向こうから右に流れる小川の音や風の音に混じって、時折水がチューブから水盆に入り音を立てた。木の間に白木の六角形の傘のような物体、左側の幹には濃い朱色の傘が見える。木材は放射状にカットして配置され、円形の外に集約点を持つ形で南を向き、ちょうどギャラリーの方向を指し示していた。

ギャラリーで「観測される気球 」は中央に浮かんで見え、バルーン下のデバイスは緑や紫の光を点灯させ、2つの黄色のプロペラが不規則に回転し、高いモーター音がかすかに聞こえていた。時折ボトルの口からは霧が出て、ヒバの香りが広がっていった。その下には、コンポスティングで制作された土(*1)である「大地」が置かれ、水と土の循環を思わせた。

「離島」は「観測される気球」を見つめるように水のテラスに配置された。ちょうど庇の真下に、ねぶた祭りで使用される手振り鉦が位置し、落ちる雨だれによって音が鳴る。静かな日には、池から離れて見えなくなるほど遠くからも澄んだ金属音が響いていた。

「サイト」からは見えないが、東の方向の急傾斜の上には水神である十和田神社の祠の跡が残されている。ぬかるむ土の上で作品制作をしながら、三原は神殿を作っている感覚だと話した(*2)。他者に関心を寄せるための場として神社が機能するように、鑑賞者は森に佇むことで、自らの敏感さが研ぎ澄まされ、圧倒的な自然を見ることになるだろう。ただ、本作で示されるのは、他者に対する感覚的・原初的な対話の方法ではなく、自然環境と人間自らがつくり出したものと仕組みも含めた総体的な環境に対峙する場である。

「サイト」と「観測される気球」はそれぞれが現地のデータを取得し、それぞれのデバイスに備わったアンテナからインターネット(3G経由)を介してリアルタイムに交信していた。更新され続ける計測データは、互いを動作させるトリガーの関係にあった。「サイト」には温度、湿度、光、風を取得する環境センサ、そして恒温動物の存在を温度で感知する焦電センサが、「観測される気球 」にも焦電センサのみ組み込まれており、ギャラリー内の体温を持つ全ての存在を捉えていた。

「サイト」の水盆へ小川から水が汲み上がる時は、ギャラリースペースに何らかの存在が訪れている時である。「観測される気球 」の下部のタンクからヒバ水の霧が出る時は「サイト」の濃い朱色の傘を被った焦電センサに何らかの存在が感知された時である。警告音のように甲高く鳴るプロペラからの通奏音は、毎秒ごとの変化を伴う風のデータを精緻に反映させるための制御信号が起こしていた。元になる「サイト」の空気の流れは、白木の傘の下に水平に60度ずつ6方向に設置された小さなマイクが計測している。超低周波音としての風の時間的差分に基づいて風向及び風力を算出し、このデータは2軸プロペラの駆動データに変換され、正逆回転方向、及び回転数の変化としてリアルタイムで反映されていた。

「モニタリングウェブサイト」は上記で述べた「サイト」と「観測する気球」の環境情報をリアルタイムで公開していった。ほぼ10秒単位で情報が更新され、連綿と即時的に現象を見せていく透明性は、人体が体感するものとは真逆の厳密な敏感さを見せていく。人の存在や気配さえも数値化し・可視化されるリアルタイムな環境情報を示すことで、私たちが暮らす情報環境(監視社会)が示され、森の中の圧倒的な情報量の体感とデータを並置させていくのである。

《自然の監視、自然の生成》において、吹き出す霧や汲み上がる水、プロペラの動きといった鑑賞者が不規則な気配のように受け取る現象でさえも全て因果を持ち、世界の縮図のようなサイクルと相互作用を見せる。さらには「サイト」までの道に置いた100Wのソーラパネルはデバイスの給電を全てまかない、霧と木材には青森の特産であるヒバが使用され、部分的に開けられた穴からはその場に元から生えている木が顔をのぞかせるようになっていた。デバイスやセンサをぶら下げるための糸でさえも、「サイト」の構築中に落下して三原たちを悩ませた桑の実で染められている。作品のシステムがその場の自然環境と接続するだけでなく、素材は青森の地に、土の協働制作によって人の生活とつながり、箱庭のように世界の一部が区切られていることがわかる。

さらに、三原が当初、森の中でのコンポストトイレを構想していた(*3)ことも鑑みれば、土に還る(微生物の)時間は、核エネルギーとその燃料廃棄にかかる時間、さらには核燃料サイクルの実現という非現実性を浮かび上がらせる。コンポスティングにおいて、土の生成のために、微生物の幸せのために従事する人間という不自然な構図は、皮肉にも物質の性質に翻弄される人の状況とも重なる。三原は、世界の一部に作品という実験場を成立させ、その内部における因果律、つまり扱われる素材や現象が真に目の前で起こすリアリティによって、現実社会の自然にふるまう非現実性に言及していくのである。

「離島」は「監視」や「生成」の関係性から距離を保ち、別の視点を加え、響く澄んだ音は、遠くから私たちを呼び止めるようである。その音は霧雨では鳴らず、土砂降りではかき消され、人間の閾値を超えた他者の言語を思わせた。また思えば、会期最終週に予期せず不調が続いたとき、暴走したプロペラの回転は、作品の因果律から生起する言語の萌芽だったのかもしれない。三原は、私たちが身を置く総体的な環境を巨視的・微視的に俯瞰するための実験場をつくり、そこで新しい他者の言語が目前に繁茂し始めるときを、一観測者として眼差していくのである。

(*1)協働制作「青森で食べたものが青森で土になる」、本カタログp. 36-38

(*2)アーティストとの制作中の会話から。

(*3)構想時のスケッチは本稿下に記載。当初中央に開ける予定だった穴の名残が、「サイト」上の水盆下に位置している。

自然の監視、自然の生成 -人工物1 サイト

自然の監視、自然の生成 -人工物2 観測される気球

自然の監視、自然の生成 -人工物2 大地

自然の監視、自然の生成 -人工物2 離島

《自然の監視、自然の生成》

ヒバ、土、センサ、インターネット、ソーラーパネル、モータ、ポンプ、糸、バルーン、手振り鉦

2019

以上全て 撮影:山本糾