Exchange-種を植える

2013年10月26日(土)~12月15日(日)

air2013-3ja

ヨーグ・オベルグフェル

Jörg OBERGFELL

《THINGS FROM ANOTHER TIME, THIS PLACE AND A RELAED PERSON.(別の時代からのもの、この場所からのもの、そして親族からのもの)》 撮影:山本糾

大勢から逃れる小さな歪み

近藤由紀

ヨーグ・オベルグフェルの作品は、都市の政治性を象徴する構造物や都市生活を反映する廃物が利用されることで、ある種の社会構造を切り取る。一方でそれらはしばしば滑稽さ、シニカルさ、密やかさ、取るに足らないものとしての「可愛らしさ」を身にまとうことで、作品の在り様としても社会を総べる力に対峙する批判性を柔らかく内包している。

こうしたささやかであることが意識的になされている表現は、空間に対するアプローチの方法にもみられる。例えば彼の作品では、所有・占領・征服を示す目印として掲げられる旗がゴミ袋と細い木片から作られ、街角にひっそりと置かれ(fig.1)、フリードリヒが絶対的な孤独を見る者に投影させた荒野に立つ木はDIY風のコンパネの台座の上に載せられ、紙で作られる(fig.2)。そこでは征服、崇高といったオリジナルが象徴する大仰な意味内容が、しばしば取るに足らない都市の廃物といった素材を用い、縮尺を変えられて示されることでオリジナルの意味をシニカルに転倒させる。

今回展示に加えられた《From Scratch(ゼロから築く)》(2013年)は、一見摩天楼が撮影された映像作品にみえる。上空からヘリコプターで撮影されたようなカメラワークや仰々しい音楽は、高層ビル群の撮影に関するメディアの常套手段である(fig.3)。だがその正体は、周囲に生えている葦で組み立てられた小さな模型を、高層ビル群の建設計画が頓挫した空き地にぽつんと置いて撮影した映像である。映像言語によってスケール感を肥大させた模型が一転矮小化する様は、乾いた可笑しさとシニカルな虚脱感を見る者に与える。

オベルグフェルの作品における引用とオリジナルの意味の転倒は、こうしたサイズと素材の変換・置換によってしばしば行われる。素材とサイズが変換される一方で、そのオブジェは驚くほど精巧に作られ、オリジナルに対する親和性や類似性が保持されている。このようにオベルグフェルがある文脈において何かを対比的に提示しようとする場合、その対比はあからさまである一方それ以外の部分が近づけられることでその対照性が緩められ、差異はさほど挑発的にならない。さらにそこに瑣末さを意図的に取り入れることで、作品それ自体が断定的で圧倒的な主張となることから逃れようとするかのようである。この「皮肉な『文脈横断』と転倒を用いた、差異を持った反復」(1) は、ユーモラスな捻りと落差をもつパロディとしてオリジナルの優位な状況に対し批評的な距離をもつ。

今回滞在制作された《別の時代からのもの、この場所からのもの、そして親族からのもの》の引用元となったのは、アーティストの祖父が作った無数の小作品である。「Exchange」というプログラムテーマから展開されたという(2)この作品において、オベルグフェルは、祖父が作り続けていた作品の技法を真似た立体作品を制作し、それを祖父の小作品を撮影した写真とともに展示した。

オベルグフェルの祖父はいわゆる「日曜大工」で、小さな作業場にこもっ

て沢山の小作品を制作していた。それらは壁掛けのオーナメントや貯金箱、ドアストッパーなどにもなっていて、有用無用が混在しており、そのモチーフは家、ガレージ、風車小屋といったヨーロッパから出たことがないという(だが旅行にはよく行っていたという)祖父の生活圏内の様子を反映している。オベルグフェルはこの祖父に倣い、滞在制作の場所でaる青森で見つけた事物をモデルとした立体作品を制作した。ここで第一階層の交換・交流として、文字通り祖父と孫といった二つの世代の時間的な交換と、日本とドイツのそれぞれのオブジェが帯びる地域特性の違いがもたらす距離的な交換が示されている。だがこれらが並置されることで立ち現れるのは、エキゾティシズムを喚起させるほどのあからさまな差異というわけではない。

例えばアーティストの出身地であるシュヴァルツヴァルトの伝統的な家

(fig.4)や青森の片側だけが長い切妻屋根を持つ家は、それぞれの域特性を反映しているが、近代的なそれらの住宅はヴァナキュラー建築というほどでもない。橋(青森ベイブリッジ)やACACの建物はしばしばこの地域を指し示すが、グローバリズムによってある程度均質化されおり、ヴァナキュラリズムが失われた近代的な小都市が新しいシンボルとして取り立てている建造物に過ぎない。死んだタヌキはドイツにだっているだろう(fig.5)。こうしてみるとオベルグフェルが選んだ「ヴァナキュラーなオブジェ」(3) は、その地域でよく見かけるものではあるが、ある種の同時代性により場合によっては差異より類似の方が目につく。

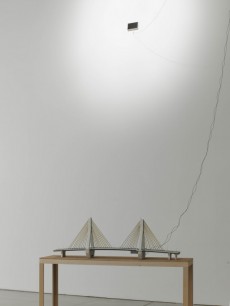

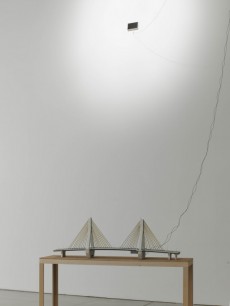

一方オベルグフェルが似せようと苦心した立体作品は、祖父に倣った拾

い集めた松葉で装飾された屋根や、粗野な風情の着色にも関わらず、厳密な縮尺による模型化と細部まで正確にコピーされた緻密で精巧な作りのせいで建築マケットのようにもみえ、それが祖父の小作品とは同一化し得ない違いを浮かび上がらせる。またそのモチーフの選択も同様で、例えばソーラーパネルに人工灯をあてることによって動力を得ているオベルグフェルの橋は(fig.6)、祖父のソーラー電池で回転する風車小屋の作品(fig.7)から着想を得ている。だが単に車輪を回す動力としてソーラー電池を扱った祖父とは異なり、オベルグフェルのそれはエネルギーの皮肉な転換方法に対するシニカルな置き換えである。オベルグフェルのこうした選択は、美術史的な意図のあるオブジェと祖父のそれを分ける。このように注意深く制作方法が模倣されたオベルグフェルの立体作品は、一見彼の祖父が作ったかのようにみえるが、そこには明らかに訓練された手と目が介在しているのがわかる。これに比べるとアーティストの祖父が作った小作品は確かに技術的ではあるが、ブリコラージュ的な技法が与える表面的な印象のみならず(それについてはアーティストも同様に制作しているのだから)、趣味の物作り特有の対象の気楽な選択や提示、制作に対する開け広げな態度がみてとれる。しかし素朴なこれらの小作品は、一方で魅力的であり、アール・ブリュット的な奔放な創造力を感じさせる。

美術という文脈でこれらが並置される時、それはしばしばアーティストが作った作品と愛好家がアーティストの独創性や方法論を模倣して二次創作的に作った作品という二項対立が示されるが、ここではアーティストが祖父をまねることで、逆にそのアーティストが特権的にもっていると考えられている手や目が、制作されたオブジェにまがい物感を与えている。祖父と孫の交換・交流は単なる世代間交流を示すのではなく、アマチュア制作者の制作態度とアーティストのそれを対比的に示すと同時に、両者の作品の価値がこの作品の文脈において、美術館という場において交換されている。

この価値の交換は、一方で必ずしも芸術対非芸術の二項対立に対する文脈主義的な提示ばかりではないようにも思える。祖父の制作過程を追ったいわば伝記的な要素もあるこの作品は、オリジナルの意味性をシニカルに転覆するというよりは、深い敬意をもって反復されることでその創造的な価値を浮かび上がらせている。両者の間にあるのはシニカルな落差ではなく真摯に継承された創造性である。滲みでた微細な差異は還元不可能な価値として対等に並んでいる。

(1) リンダ・ハッチオン『パロディの理論』、辻麻子訳、未来社、1993年、78頁。

(2) ヨーグ・オベルグフェルのへのインタビューより(2013年12月10日ACACにて)。

(3) ヨーグ・オベルグフェルが展覧会の解説資料に寄せた文書より。

撮影:山本糾

fig.1 《旗》、プリント、60x150cm、2010年。

fig.2《孤独な木(カスパー・ダーヴィット・フリードリヒにもとづく)》、枝、ベニヤ、印刷物、36x24x14cm、2011年。

fig.3 《ゼロから築く》(キャプチャー画像)、2013年。

fig.4《(両親の家にあった)壁紙で作った屋根のある黒い森の家》、写真、2013年。

fig.5 《たぬき》、オブジェ、2013年。

fig.6 《ベイブリッジ》、オブジェ、2013年。

fig.7 《ソーラーパネルのある風車小屋》、写真、2013年。

《ゼロから築く》展示風景 撮影:山本糾

Exchange ―Planting the seed

October 26 – December 15, 2013

Jörg OBERGFELL

ヨーグ・オベルグフェル

THINGS FROM ANOTHER TIME, THIS PLACE AND A RELAED PERSON. photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

Small distortions to escape from the mainstream

KONDO Yuki

Using constructions that symbolize city politics and/or discarded articles reflective of city life, Jorg OBERGFELL exposes a kind of social structure in his work. At the same time, wrapping them up in “cuteness” related to humor, cynicism, secrecy and trifles, he makes his work, in its overall image, gently involve criticism that faces the power controlling society. His style of intentionally expressing such modesty is also seen in his approach to deal with space in his work. For instance, a flag hoisted to represent possession, occupation and conquest is made of a garbage bag and a thin wooden stick (fig.1). In another work, a lone tree standing in a wilderness, which is viewed as reflecting Friedrich’s absolute solitude, is placed on a DIY plywood pedestal and constructed out of papers (fig.2). Here, again, the exaggerated meaning and content of the original such as conquest and sublimity are shown cynically inverted on a totally different scale by using useless things in the city as materials.

At first sight, “From Scratch” (2013) included in this exhibition looks just like an image of filmed skyscraper. The camerawork, which makes us think that the picture might be taken from a helicopter up in the sky, and grand-sounding music are usual tactics for the media to film high-rise buildings (fig.3). Actually, however, the artist’s subject is a small model made of reeds growing nearby, placed all by itself in a vacant lot where the plan of constructing a cluster of high-rises has come to an impasse. When the model that gave an impression of a grand scale suddenly shrinks to such a small-scaled object, a viewer feels a dry sense of humor and cynical despondency as well.

In Obergfell’s work, quotes and inversion of original meanings are often handled through conversion and replacement of the size and materials. While he changes the size and materials, he creates the object with amazingly exquisite workmanship maintaining the affinity and similarity with theoriginal. When he thus presents the object for contrast in a certain context, he deals explicitly with the contrast, but at the same time, he deliberately uses all elements other than contrast in order to ease differences so as not to give a provocative impression. In addition, incorporating trivia on purpose, he seems to try to avoid giving an overwhelmingly assertive image to his work. Repetition with a difference in its ironic ‘trans-contextualization’ and inversion(1) keeps a critical distance to the predominant original as a parody with a humorous twist and difference.

To produce his work entitled “Things from another time, this place and a related person” for the artist-in-residence program here, the artist borrowed ideas from countless small pieces made by his grandfather. Based on the project theme “exchange,”(2) Obergfell produced three-dimensional works following the technique that his grandfather used and exhibited them together with photographs of his grandfather’s pieces. His grandfather, so-called Sunday carpenter, used to shut himself up in his small workplace to make lots of small articles, useful or not, including wall ornaments, piggy banks and doorstops. The motifs such as house, garage and windmill represent familiar items in his daily life. (His grandfather stayed in Europe throughout his life, though he often enjoyed travelling.) Following his grandfather, Obergfell produced three-dimensional works based on things, which he came across in Aomori, the site of the residency program. Here is literally the first-level “exchange” in terms of time between two generations, grandfather and grandson, and also in terms of space between Japan and Germany with objects having different regional features showcased respectively. You might note, however, that those objects placed side by side are not indicative of such substantial disparity as to evoke exoticism. Here is an example. A traditional house in Schwarzwald, the artist’s hometown (fig.4), and a house in Aomori which has a long gabled roof only on one side reflect the distinguishing features of the district respectively, but it is hard to call those modern houses vernacular architecture. The bridge (Aomori Bay Bridge) and buildings of ACAC often represent this area, but they are built uniformly to some extent due to globalization. They are nothing more than constructions promoted as a new symbol of a modern small city where vernacular traditions are no longer observed. Probably there are dead raccoon dogs (tanuki) in Germany, too (fig.5). Thus viewing “vernacular objects” (3) chosen by Obergfell, similarities draw more attention than differences in some cases owing to a contemporary quality, though they are often seen in specific areas. For some three-dimensional pieces on which he worked hard to imitate the original, the roof is decorated with collected pine needles as his grandfather did and the coloring is made rough. As the artist correctly copied the old pieces in detail and structured precisely and exquisitely on a strictly reduced scale, his works look like architectural models, and differences are clear enough so as not to make them look identical with his grandfather’s small pieces. The same is true of his way of choosing motifs. For example, he got the idea of his bridge (fig.6) from his grandfather’s windmill (fig.7) driven by a solar battery, but his bridge is powered by artificial light applied to the solar panel. It means, different from his grandfather who used the solar battery only to rotate the wheel, Obergfell shows a cynical inversion through an ironical conversion of energies. This process he has chosen separates his objects, which are to be interpreted in terms of art history, from his grandfather’s. Therefore, his three-dimensional works in which the production method has been carefully copied look as though his grandfather made them at a glance, but it is clear that well-trained hands and eyes lie between the two. Comparing them, we realize that his grandfather’s small pieces are certainly technical, but they give superficial impressions caused by such bricolage technique (the artist follows the same process), and we also notice a casual way of selection and display as in one’s hobby of making things and a frank attitude toward creation. From another viewpoint, these simple small pieces are charming like art brut showing a vivid and free imagination.

With the two kinds of works placed side by side in the context of art, we think of binary opposition: works created by artists and art-lovers’ secondary pieces made by copying artists’ originality and methods. Obergfell’s works, however, are made by copying his grandfather’s pieces with his privileged hands and eyes, and that gives those works a fake impression. The “exchange” between him and his grandfather does not simply indicate the exchange between generations but also an amateur artist’s attitude is shown in contrast to that of a professional artist, and values of their works are exchanged at the site of an art museum in the context of these works.

The exchange of value is not necessarily expressed in the contextual-based picture of binary opposition, art vs. non-art. This work, which incorporates a biographic element tracing his grandfather’s production process, reveals the value of creativity as he respectfully repeats the meaning of the original rather than cynically inverts it. What lies between the two is not a cynical gap, but creativity succeeded earnestly. Small differences seeping through them seem to be confronting equally with each other as irreducible values.

(1) Linda HUTCHEON, “A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms,”(New York: Methuen, 1985).

(2) Interview with Jorg OBERGFELL on December 10, 2013 at ACAC.

(3) From Obergfell’s text for the exhibition catalogue.

photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

fig.1 Flags, pigment prints, 60x150cm, 2010.

fig.2 The Lone Tree (after Caspar David Friedrich), branch, plywood, print media, 36x24x14cm, 2011.

fig.3 From Scratch (captured images),2013.

fig.4 black forest house with roof made of grass wall paper (from my parents'living room), photo, 2013.

fig.5 racoon dog, object, 2013.

fig.6 bay bridge, object, 2013.

fig.7 windmill with solar powered sail, photo, 2013.

From Scratch, installation view. photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu