trans×form ─かたちをこえる

2013年7月27日(土)~9月16日(月・祝) 10:00-18:00 / 無料

air2013-2ja

マニシャ・パレク

Manisha PAREKH

《影の庭》、2013

サイズ可変(100点組)

シナベニヤ、丸棒木材、インドシルク

撮影:小山田邦哉

日常と創造のための変奏

近藤由紀

青森で「蕗」は「ばっけ」と呼ばれ、春から夏にかけて至る所で群生している。郊外にあるACACでは、アーティストたちが滞在制作を始めた6月には、青々と巨大化した葉を広げ、緑豊かに地面を覆っていた。

マニシャ・パレクの滞在制作作品には、ACACの環境や青森で出会った事物からの直接的な反応が反映されていた。《Shadow Garden(影の庭)》は、群生する蕗がモチーフとなっている。蕗の葉の輪郭を捉えたドローイングを直接板に描き、それを2枚ずつ切り取ることで、描かれた形とその鏡像を得る。そうして切り取られた100枚の板には、「虫食いの穴」として小さな穴がドリルによって線状に穿たれている。もう一つの5枚組の作品《Gratitude(謝意)》では、環境の印象を示す雨、霧、木、日、山の5つの漢字がモチーフとして用いられている。支持体は藍によって染められており、それは近代以前に青森でよく着用されていた藍染めによる古い着物(こぎん刺しの作業着など)が視覚的な参照となっている。こうした反応は一方で、滞在制作だけがその理由ではない。パレクはしばしば自らが置かれた環境の外的な要因やそこでの印象や記憶、あるいはその場所に関わる素材を意識的に取り込み、それらをミニマルな形によって抽象化することで作品を制作している。

日本で紹介されるインドのコンテンポラリーアートは、自国の政治的・社会的状況を背景にしたり、物語性と具象性の伝統を反映したりした作品が多い。実際そうしたインド以外の国によってコード化された「インド的要素」を取り込むことは、国際的なアートシーンにおける戦略でもあるのだろう。そうした状況の中、マニシャ・パレクは、私的な記憶や無意識を背景に還元的で抽象的な傾向をもつ作品を制作している。それはインド絵画における具象的・物語的絵画の大きな流れの中で幾何学的な抽象表現を追求し続けたナスリ―ン・モハマディ(1937-1990)にも連なる。

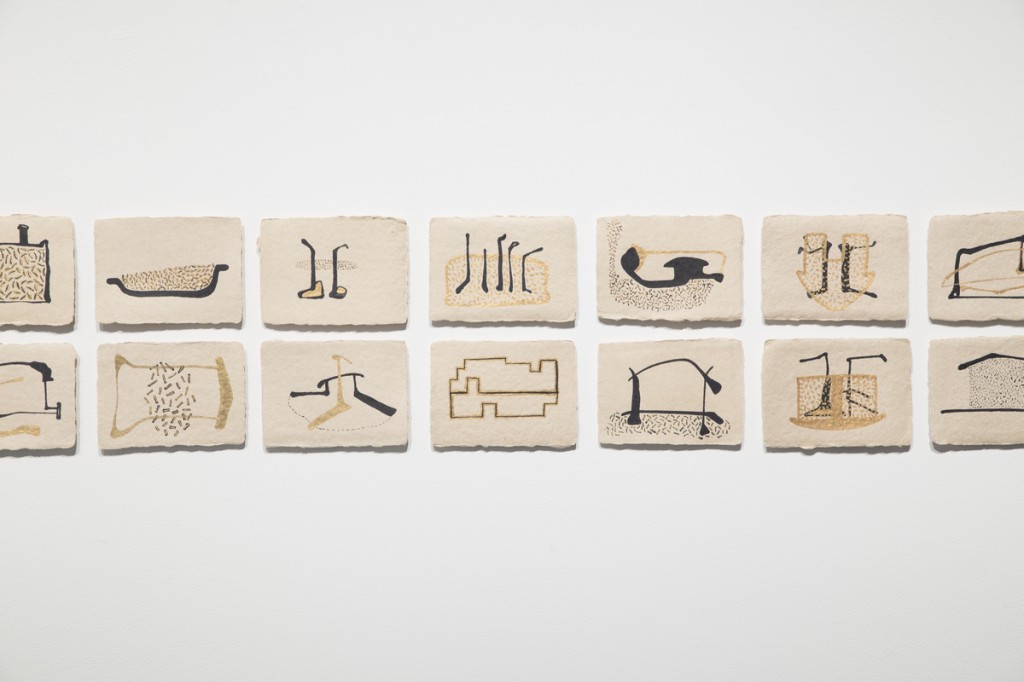

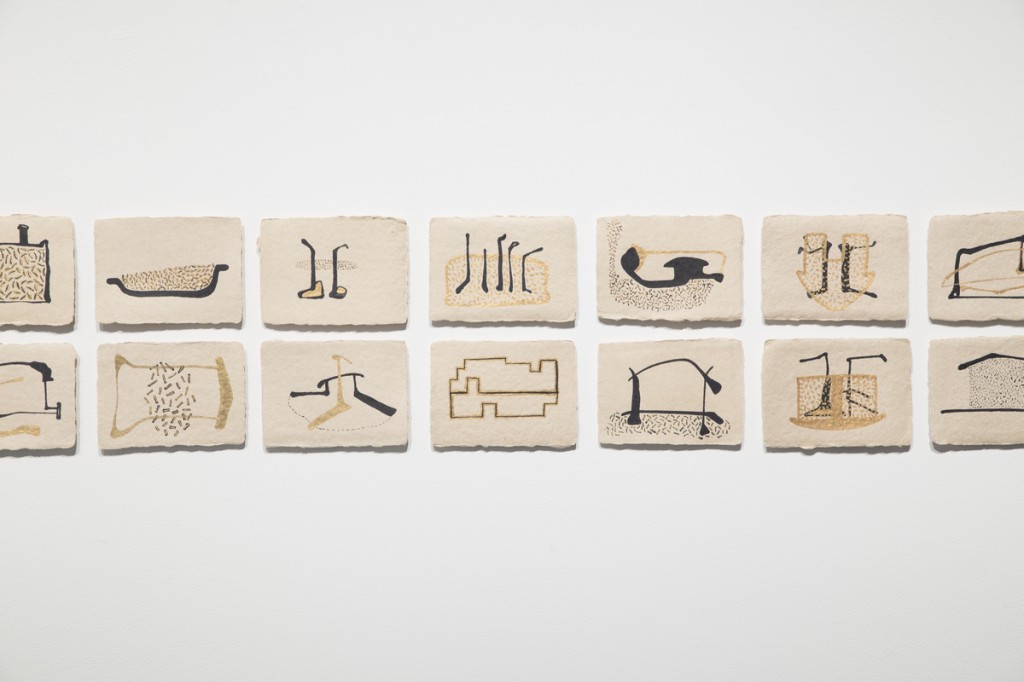

パレクの抽象は、記憶、体験、経験といった彼女の身近な事柄の抽象化であり、そこには作家独自の類似のシステムが機能している。さらにこれら私的なイコノグラフィは有機的に発展するシリーズ作品あるいはマルチプル作品として示されている。例えば今回一緒に展示された《Nesting(巣作り)》(2011年)は、50枚組のドローイング作品である。手漉き和紙に描かれた、墨と金の染料によるドローイングは、バイオモルフィックでもあり、図形的でもある。これはパレクが自分のスタジオを建設している時期に描かれた作品であるという。小さな細胞を思わせるそれらの図像は時折間取り図のようにも見え、タイトル通り自らの小宇宙であり、快適な居場所である作家のスタジオ建設という「巣作り」の過程を反映しているということをうかがわせ、一種のヴィジュアル・ダイアリーの様相を呈している。参照となった対象を探ることはさほど重要ではないが、パレクの制作の態度として、周囲の環境に敏感に感応し、それを内側に取り込んで形を生みだしていくというその制作の過程をみることができる。

《Nesting》はドローイングの連作からなる作品だが、同様の手法のシリーズ展開や同じような形のモチーフを積み重ねて作品を構成するということもパレク作品の特徴の一つである。こうした複数化や反復は、パレクの外的かつ具体的な視覚的参照が、内的な記憶や無意識によって変化していく過程そのものであり、それらを抽象的で還元的な形に出力するための語法として用いられている[i]。

バイオモルフィックな形態が豊かに変化していくドローイング作品は、一つの主題に基づくヴァリエーションであり、その重なりが主題に対する作者の内奥を広げていくように、一つの形から次の形を導いていくように連続的に連なっていく。一方《Shadow Garden》や《Animal》(2009年)(fig.1)、《Seed》(2009年)(fig.2)のシリーズや、今回の《Shadow Garden》との連続性も見られる《Pomegranate Bloom 1, 2, 3, 4》(2009年)(fig.3)は、ある単純な最小単位の形が反復されることで全体が構成されている。

《Shadow Garden》のほぼ同じ形に切り取られた板には支柱が添えられ、100枚分の影を色濃く落とすことで、ほぼ反復的に累積された類似の形は倍数となっている。一方でこの反復は、機械的かつ単純な反復としてではなく、「ドローイング」の一手段とみなされ、部分と全体に意図的な差異が加えられている。蕗の形をした板におけるフリーハンドによって生じた僅かな差異、パレクが「ドリルドローイング」とよぶ虫食いを思わせる線状の穴の並びといくつかの大きめに穿たれた穴に埋め込まれた赤く染められた絹布の結び目の線は、反復的な行為におけるヴァリエーションであり、モチーフの展開の一形態でもある。

ドリルドローイングと呼ばれたこれら穴をあける行為は、きっちりとした手順で機械的に穿たれていくのではなく、ある種の即興性と創意性を備えており、表出の即時的な反映と素材からのフィードバックに対する即物的な反応によって行われている。素材と行為と出来上がった形から次の形が現れてくるという点においては、ドローイングの展開と同じなのかもしれない。一方でそのヴァリエーションはある還元された形の単純な反復行為からなり、いわゆるドローイングが有する豊かな変化や自立性をもたない。《Shadow Garden》は、床面からギャラリー角に向かって上に伸びていくように設置された。形と設置の仕方によって有機的な動植物の生育を思わせる一方で、僅かな差異は抑制された表現における個性の発現を思わせ、手の痕跡を感じさせる繰り返される型は、工芸における反復を思わせる。したがってその反復は作り手の身体的な律動や動植物の圧倒的な増殖というよりは、全体として静謐な印象を与える。パレクの作品にクラフトとの親和性を見出すのは、手仕事的な印象を与える作品の現れのみならず、こうした作りと行為によるところもあるのだろう。

インドはクラフトが盛んであり、パレク自身クラフトに深い敬意を払っている。日常と密接に関わっているクラフトは、一方で手法や素材、あるいはその発生の歴史において世界と接続しうる共通言語をもっている。それはパレクが日常的な事柄や個人的な記憶や印象、感情や思考を抽象言語によって普遍化し、作品を制作することと深い部分で繋がっているのかもしれない。

《Gratitude》では、そういった関心からインドと青森を繋ぐクラフト的な共通言語としての藍染(インドは最も古い藍染めの中心国の一つである)と近代以前の衣服に施される装飾性と機能性を兼ね備えた刺繍が取り上げられている。モチーフとなった漢字は内容としてはパレクが直接的に感応した自然現象を示す文字ではあるが、一方でそれらは図像的・視覚的な体験として扱われている。一見黒に近いほど濃い藍染めがなされ、反転された文字の上には、ライン上になったドリルドローイングが施されているため、文字は藍とドリルの穴に沈み、一見すると紙に書かれた文字というよりは、布のような不思議な質感を獲得し、古い着物のようにもみえる。クラフト的関心から制作された作品は決してクラフトと同じ手法では作られてはいないが、様々な過程を経て、思いがけず工芸との質感的類似を獲得したのは偶然に拠るばかりではないだろう。

パレクの作品は、横と奥に広がっていく印象がある。横は例えば獲得されたヴァリエーションの形、反復の形、複数化することで物理的に空間に広がっていく形である、それら自体にはしばしば深みがなく、日常の表層面あるいはクラフト的な手仕事の均一感をも感じさせる。それと同時に、穴、ドローイングにおける線、平面作品におけるマチエール、立体化した作品が落とす影などが非物理的な内奥へと導くようで、その両方が作品上でせめぎ合っている。虚実皮膜ではないが、それは日常と非日常、現実と夢想、意識と無意識、労働と創造などの間の薄皮をも指し示すかのようである。

[i] マニシャ・パレクへのインタビューより(2013年8月17日ACACにて)。

***

滞在制作作品

《影の庭》、2013

《影の庭》、2013

サイズ可変(100点組)

シナベニヤ、丸棒木材、インドシルク

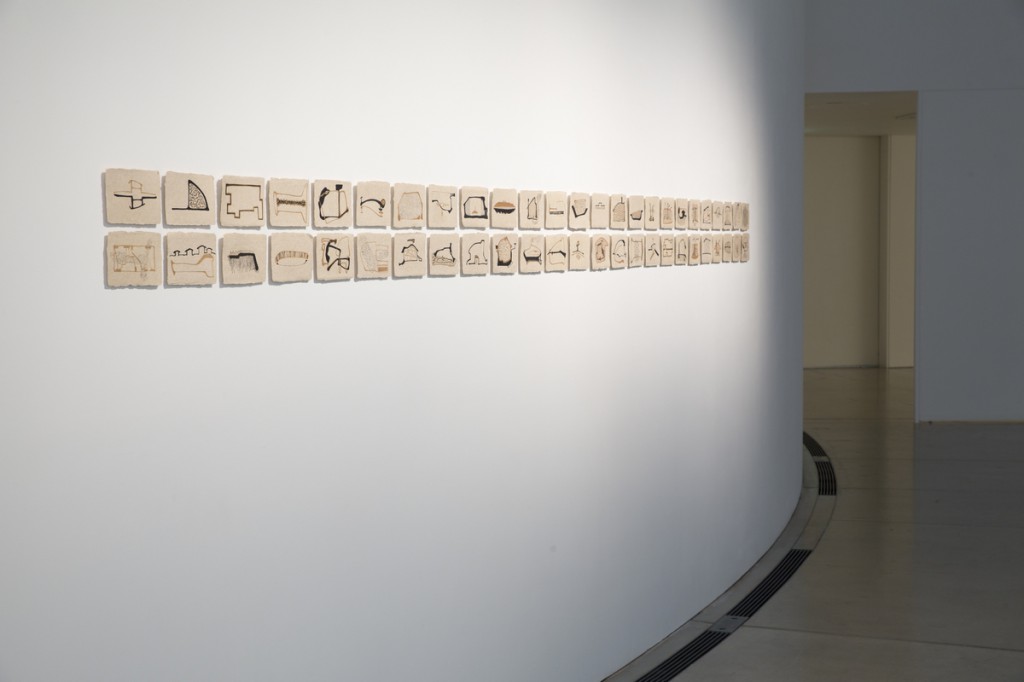

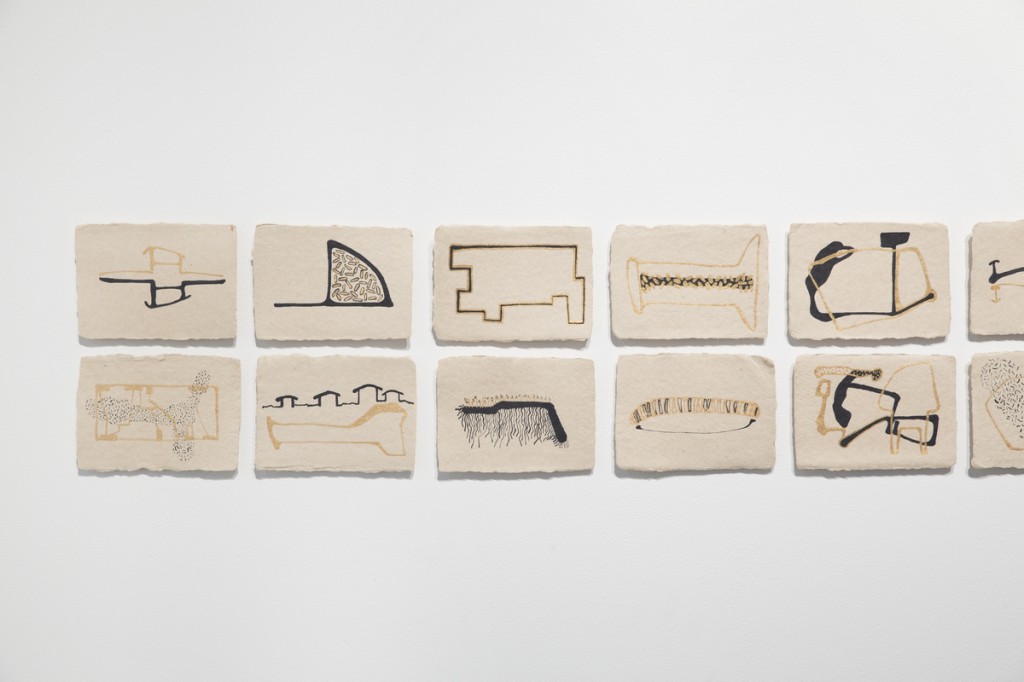

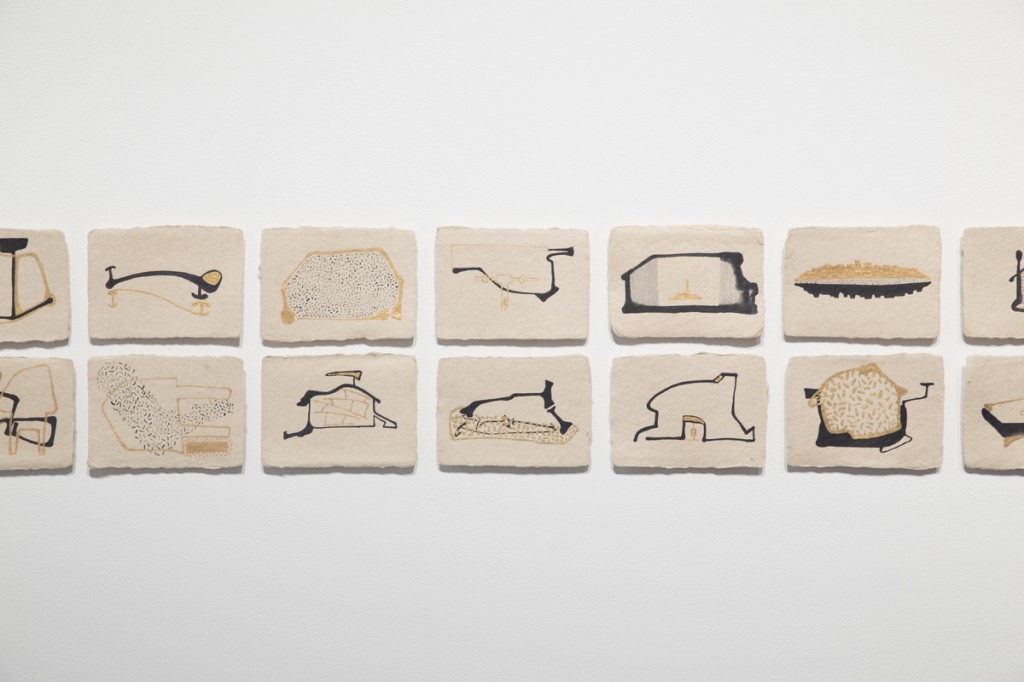

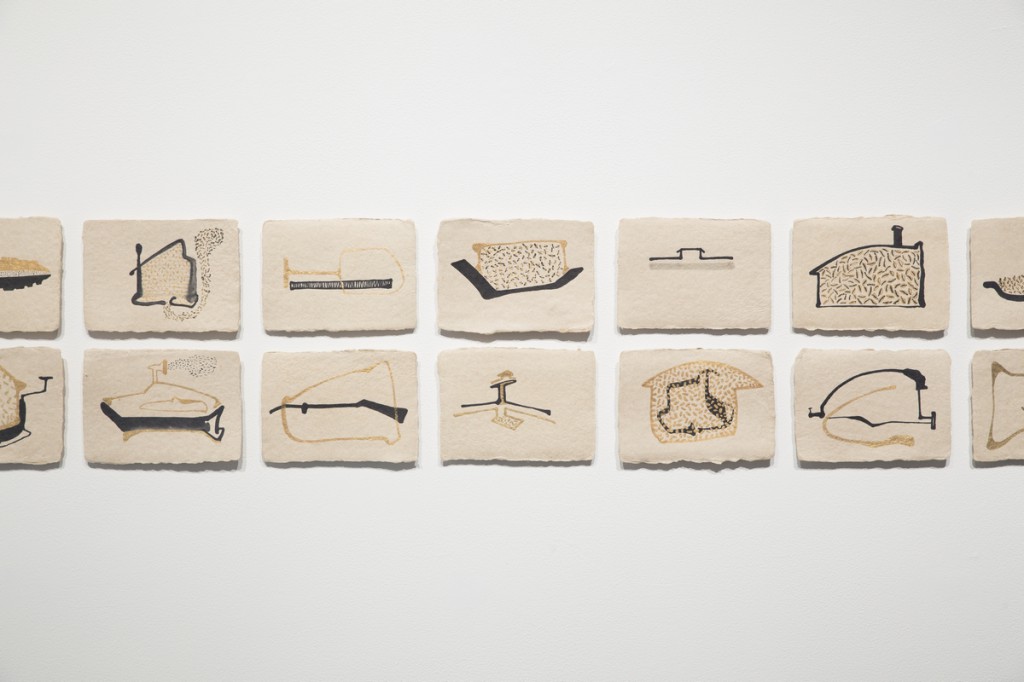

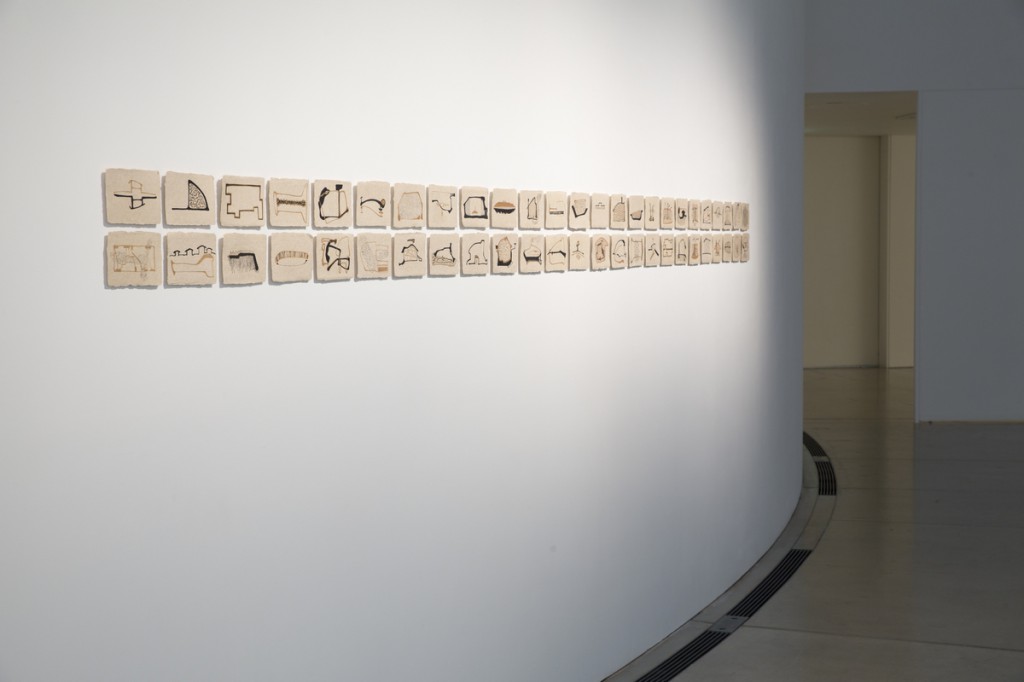

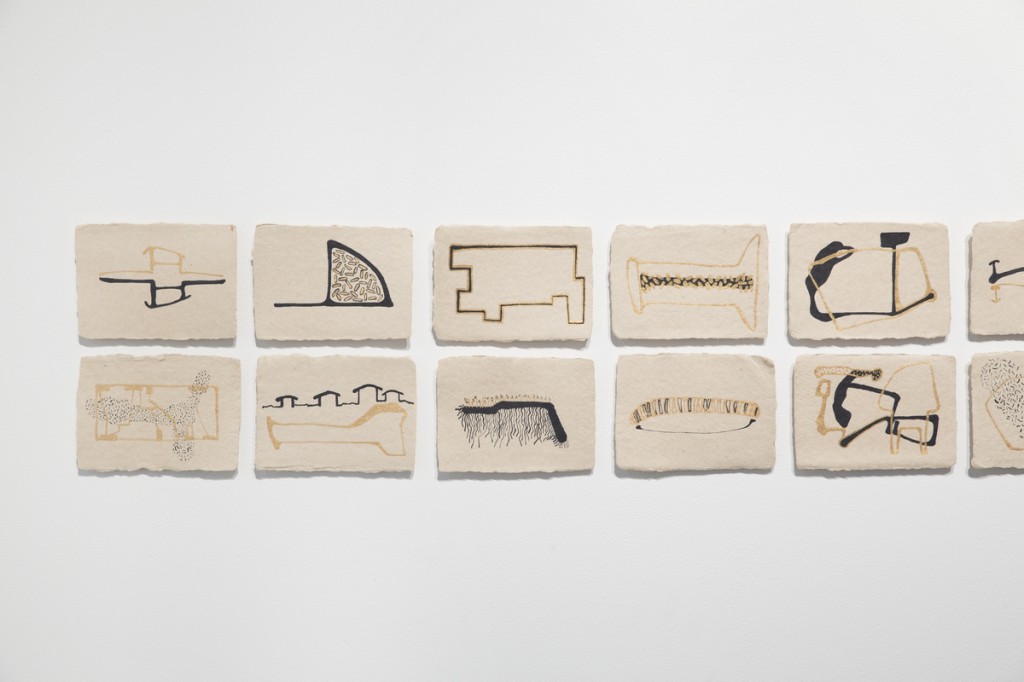

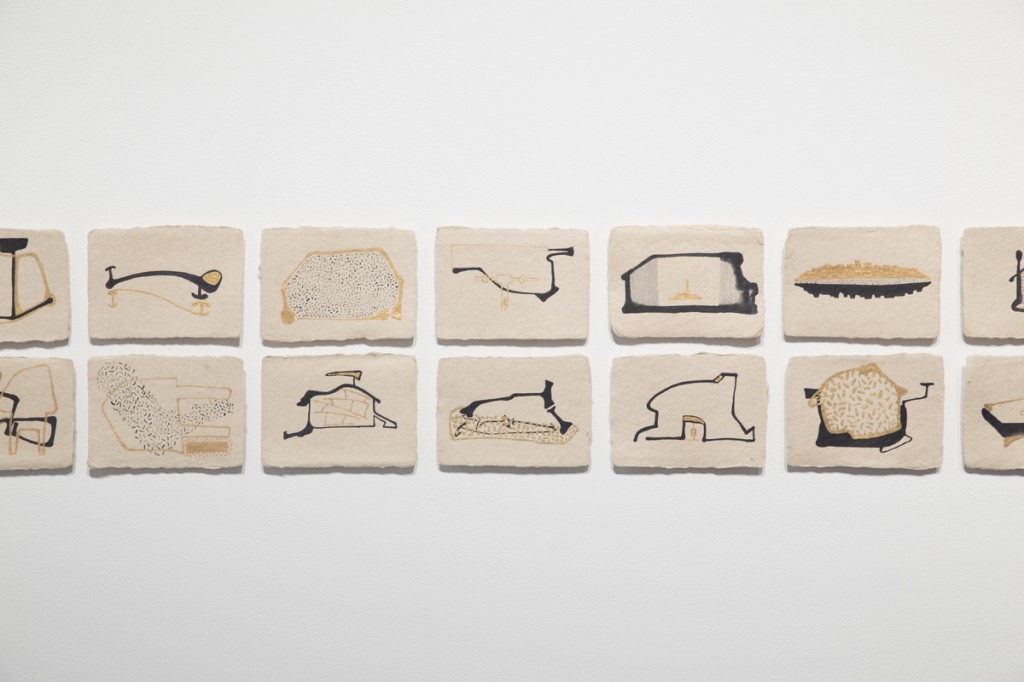

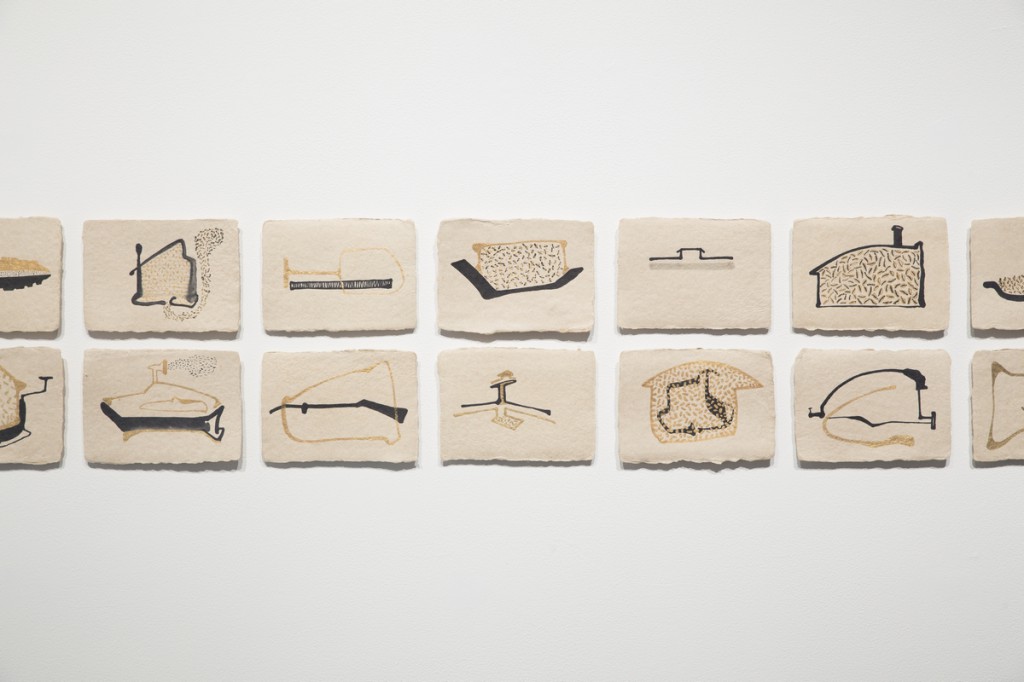

《巣づくり》、2011

《巣づくり》、2011

W150×H110mm(50点組)

インド製手すき和紙、墨汁、グァッシュ

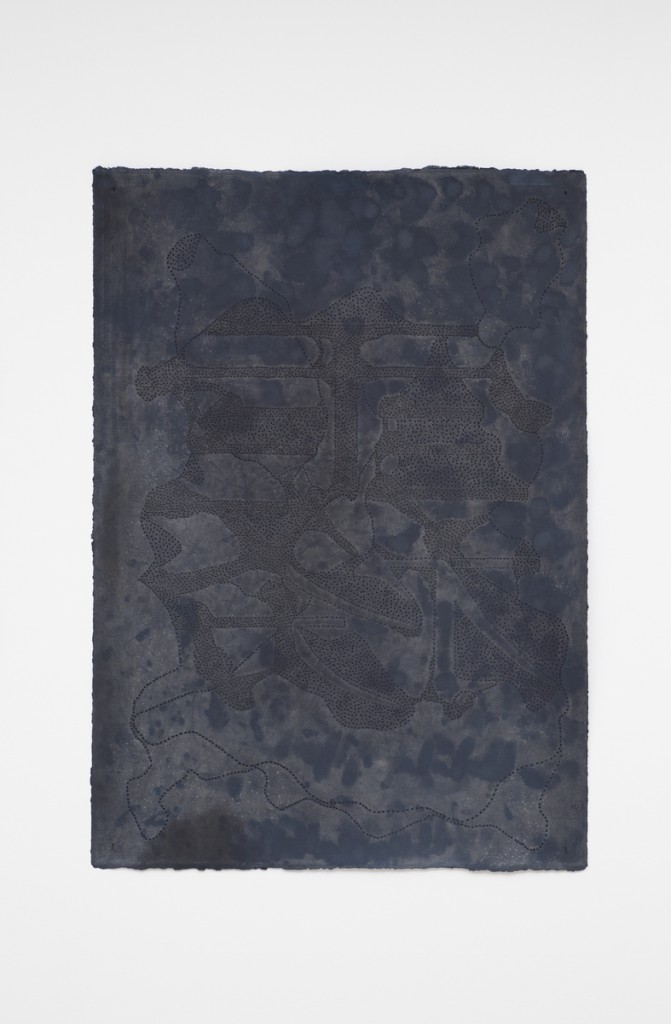

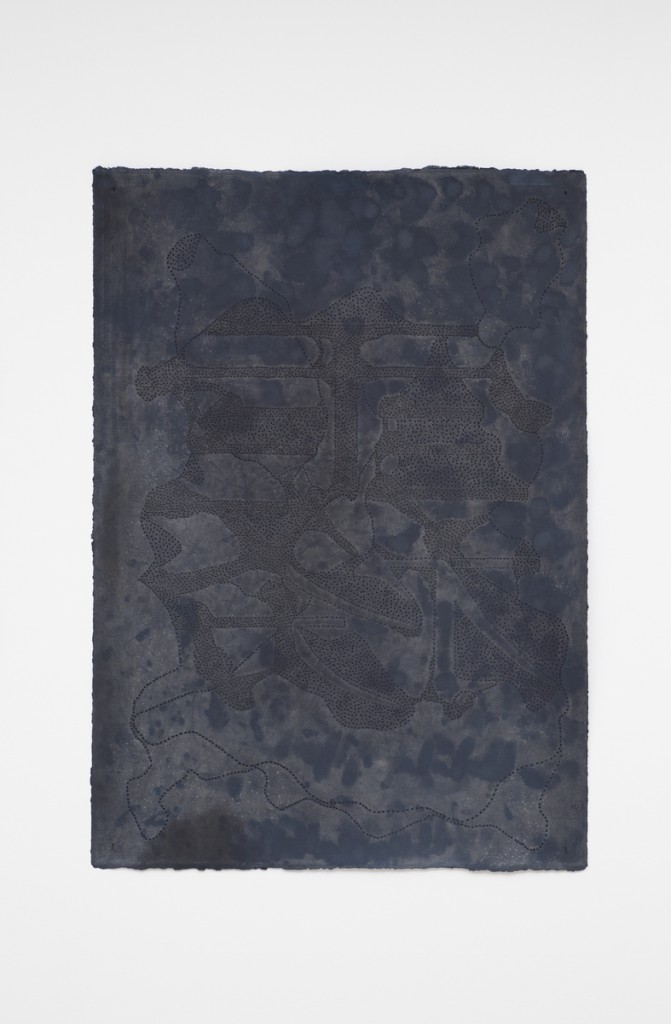

《謝意》、2013

《謝意》、2013

W750×H1050mm(5点組)

アルシェ紙、藍、墨

撮影はすべて小山田邦哉

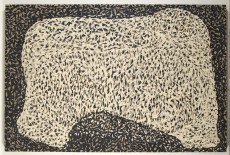

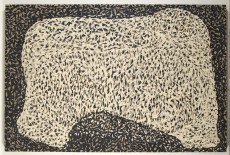

fig.2《Seed(種)》、2009

183x122cm

板に手漉き紙

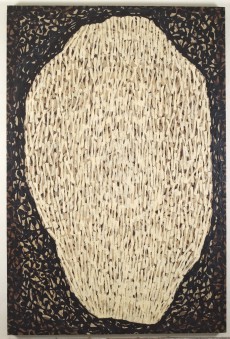

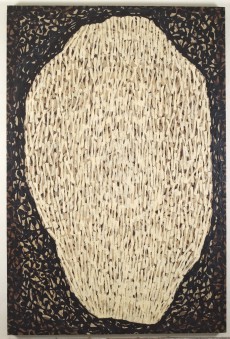

fig.1《Animal(動物)》、2009

122×183cm

板に手漉き紙

fig.2《Seed(種)》、2009

183x122cm

板に手漉き紙

fig.3《Pomegranate Bloom(ザクロの開花) 1, 2, 3, 4》、2009年

各91x91cm

板に手漉き紙と絹(4枚組)

trans×form

10:00am - 6:00pm, July 27 - September 16, 2013 / Admission Free

Manisha PAREKH

マニシャ・パレク

Shadow Garden, 2013

Dimension variable (100 units)

Plywood, Wood, Silk

Photo: OYAMADA Kuniya

Variations for Daily Life and Creation

KONDO Yuki

In Aomori, the giant butterbur (fuki) is called bakke, and can be seen clustering from spring to summer. Aomori Contemporary Art Centre (ACAC) is in the suburbs and in June when the artists started their residencies, the butterbur were spreading out their verdant, enormous leaves and covering the ground in lush greenery.

The work produced during Manisha PAREKH’s residency reflects a direct response to the things she encountered in the environment of ACAC and Aomori. Shadow Garden takes these bunches of giant butterbur for its motif. Parekh did a drawing of the silhouette of the butterbur’s leaves directly onto a wooden board and then by cutting out two each she could get both the form of what she had drawn and also its mirror image. Onto 100 boards cut out in this way, small holes were drilled in lines as holes “eaten” by insects. Another work, Gratitude, was made up of five parts and used the five Kanji characters for rain, mist, tree, sun, and mountain as motifs to show impressions of the environment. The base was dyed blue, a visual reference to the indigo-dyed kimonos used in pre-modern Aomori, such as in kogin-zashi needlework. These responses did not occur simply because she was producing work during a residency, but through Parekh producing an artwork by consciously assimilating the external factors of the environment in which she frequently finds herself, as well as her impressions and memories of it, or otherwise the elements associated with that place, and then abstracting these through making them into a minimized form.

The Indian contemporary art that is showcased in Japan is often art placed within the context of India's political and social circumstances, and that reflects the traditions of the narratological and the figurative. In fact, assimilating these “Indian elements” codified by countries other than India is surely a strategy within the international art scene. Manisha Parekh, though, is creating artworks that tend towards the reductive and the abstract, against a backdrop of personal memories and the unconscious, and this connects with Nasreen MOHAMEDI (1937-1990), who pursued geometric and abstract forms of expression within the large drifts towards figurative and narrative work in Indian painting.

Parekh’s abstractions are those close to her memories and experiences, and here her own analogical system is functioning. This personal iconography is expressed as multiple artworks or an artwork series that develops organically. For example, exhibited with her new work for this program was Nesting (2011), a drawing work made up of 50 pieces. The drawings were made using ink and gold dyes on handmade paper; they are biomorphic, figurative. It is apparently a work made by Parekh in the period when she was building her own studio. The icons evocative of small cells also occasionally look like floor plans; they are literally her own small universe. They offer glimpses of how she is reflecting the process of “nesting” that is an artist’s studio in a cozy place, presenting a kind of visual diary. Searching for the subject that was her reference is not so important, but we can see the process of production in how she responds sensitively to her surroundings as her attitude towards producing work, assimilating it internally and creating a form.

Nesting is a work made up of a series of drawings; one of the features of Parekh’s work is composing artworks by developing a series in the same method or aggregating similar motifs of forms. This multiplication and repetition is a part of the process whereby Parekh’s external and concrete visual references transform through her internal memory and unconscious; it is used as language for delivering these references in an abstract and reductive form.[i]

The biomorphic configuration of the drawing work transforms richly, a variation based on a single main theme, with one form leading consecutively on to another, as if the overlapping is upholding the artist’s inner depths towards the theme. On the hand, the entirety of Shadow Garden, Animal (2009) (fig. 1) and Seed (2009) (fig. 2) series, and Pomegranate Bloom 1, 2, 3, 4 (2009)—which seems to be a continuation of Shadow Garden—are all composed by repeating a simple form of the smallest unit.

With a supporting post attached to wooden boards cut out in almost the same shape as those in Shadow Garden, the analogous shapes accumulated almost repetitively become multiples by casting a deep shadow from the 100 pieces. On the other hand, this repetition is not a mechanical replication; rather, it is being regarded as a part of the “drawing,” supplementing an intentional difference to the part and the overall. These bare differences born out of the artist’s work by hand on the butterbur board base—what Parekh calls “drill drawing,” lines of holes evocative of bug holes, along with some larger holes, all embedded with knots of silk dyed red—are differences in a repetitive form, as well as the development of a motif.

“Drill drawing,” the act of making these holes, is not a strict procedure nor is it boring mechanically. It is laid out with a kind of improvisation and creativity, conducted through physical responses to the materials and immediate expressive reflections. In how the form made from the material and action manifests itself as the next form, its flow corresponds to the development of drawing. On the other hand, these come out of the simple act of repeating a reduced form, and do not possess the rich transformations or independence that drawings have. Shadow Garden is set up facing the gallery from the floor, extending upward. While on the one hand it evokes the organic seeding of flora and fauna through its form and set-up, more than the physical rhythm of the artist, the overwhelming propagation of plants and animals, these slight differences evoke the reiteration in craftwork as restrained expression and personal exhibiting, conveying a tranquil impression. Discovering this affinity with crafts in Parekh’s work is not only in the presence in the work that gives an impression of being “made by hand,” but is also likely there in how it is made by these kinds of actions.

Crafts are popular in India and Parekh herself respects crafts very much. Crafts intimately related to everyday life possess a common language where they can connect with the world in the techniques of weaving, sewing, and dyeing, in materials, or in the history of their emergence. This probably connects deeply to how Parekh is universalizing everyday matters, personal memory, impressions, and emotions through abstract language, and then creates her artworks.

In Gratitude, indigo dyeing (India is one of the oldest of the major countries with indigo dyeing) and the careful embroidery employed on pre-modern clothing are taken up as craft-like common languages for connecting India and Aomori from this interest Parekh has. The Kanji character motifs are words showing, as content, the natural phenomena to which Parekh has directly responded sympathetically, and on the other hand they are also being dealt with as iconographic and visual experiences. Due to the “drill drawing” along the lines, on the inverted words indigo-dyed so deep they almost seem black at first the words have sunk into the indigo and drilled holes, meaning at first they seem less like characters drawn onto paper than old kimono, acquiring a cloth-like texture. The artworks produced from this craft-esque interest are not in any way being made with the same methods as crafts, but that, through a range of processes, Parekh stumbles on and acquires this textural analogy with crafts surely cannot be merely accidental.

Parekh’s artworks have the impression of extending to the sides and the back. The sides possess a form that extends out physically into the space, for example by multiplying the form of the acquired variations or the repeated form, and while these do not have much depth, they evoke the surface of the everyday or a craft-like handiwork sense of evenness. Simultaneously, the holes, the lines on the drawings, the materials on the two-dimensional works, and the shadows cast by the three-dimensional works and so on all lead one to an immaterial inner depth, and both of these aspects are competing in the artworks. While not a membrane of the true or the false, it is perhaps pointing us towards that thin layer between the ordinary and extra-ordinary, reality and daydream, conscious and unconscious, labor and creation.

[i] Interview with Manisha PREKH (August 17th, 2013, ACAC).

***

Photos of the works in ACAC

Shadow Garden, 2013

Shadow Garden, 2013

Dimension variable (100 units)

Plywood, Wood, Silk

Fuki leaves (Butterbur), the Motif of Shadow Garden

Fuki leaves (Butterbur), the Motif of Shadow Garden

Nesting, 2011

Nesting, 2011

W150×H110mm (50 units)

Chinese ink and gouache on Indian handmade paper

Gratitude, 2013

Gratitude, 2013

W750×H1050mm (5 units)

Arches paper indigo dye and sumi ink

All photos are taken by OYAMADA Kuniya

Manisha PAREKH

Photo: OYAMADA Kuniya

fig.1 Animal, 2009

122x183cm

Handmade paper on board

fig.2 Seed, 2009

183x122cm

Handmade paper on board

fig.3 Pomegranate Bloom 1, 2, 3, 4, 2009

91x91cm (each)

Handmade paper on board and silk (work in 4 units)

All photos are taken by OYAMADA Kuniya