普遍的な風景

2016年7月30日(土)~9月11日(日)10:00~18:00 会期中無休・入場無料

千葉奈穂子

CHIBA Naoko

《時の層》

写真、2016年

撮影:山本糾

光の層を捉える

近藤由紀

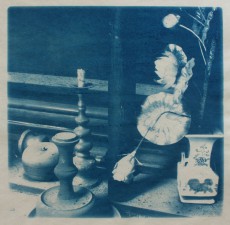

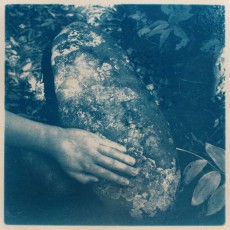

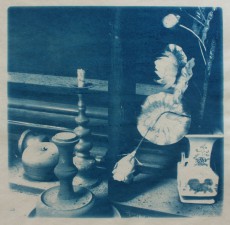

古い写真技法の一つであるサイアノタイプを使って撮影し、それを手漉き和紙の上に焼き付ける。青色の濃淡で像が現れるサイアノタイプを、機械で作られた紙とは違い、植物の繊維の長短が独特の不均一な表面を生む手漉き和紙の上に焼き付けた写真は、蒼く、少しぼんやりとしていて、鮮明さと不鮮明さの入り混じった像を現す。その風合いは写真というより絵画のようにもみえ、同時代の風景というよりは、時間のはっきりしない過去の風景か、あるいはところどころ不鮮明になった記憶の中の無時間的な一場面のようにもみえる。だがそこで撮影されている対象は、まぎれもなく今、ここにある風景だ。

千葉奈穂子は1997年から岩手県花巻市東和町にある築200年の母屋のある父方の農家とその周辺を撮影し続けている。一見のどかなこの場所は、千葉の遠い先祖が連綿と守り、耕し、400年という年月、土地と血をつないできた場所である。蝦夷のリーダー、阿弖流為の伝説やアイヌの言葉が残る土地、幾度となく冷害と飢饉に襲われた東北の土地、そこには「時間の重み」という言葉では片づけられない自然と共に生きてきた人の営みと生死の歴史が堆積している。だがその土地も時代の変化によって過去の層を忘れ去り、辛うじて過去の暮らしを伝えてきた物理的なモノたちも今まさに消えゆこうとしている。

千葉のライフワークともいえる《父の家》は、こうした土地とそこに残るモノたちを撮影し続けてきた作品のシリーズである。自らのアイデンティティをたずね、一族の土地の気配のようなものを、こぼれ落ちて行く記憶の曖昧さも含めて定着させるようにフィルムに感光させてきた作品の根底には、消えゆこうとしている過去から今にか細く続く何かを「写真」という表現手段であり、また記録媒体でもあるメディアによって、それらの事物を取り巻く目には見えない空気ごと残そうとする関心をみることができる。

家族の歴史を追うことから始まったこの制作が次第に東北という土地の古層を探ることへと展開していったのは当然の帰結といえるだろう。2014年から千葉が参加しているプロジェクト「精神の北へ」において、千葉は福島でヨーロッパの北方都市に住むアーティストたちとともに滞在制作をしながら、北に住む者たちの文化や生活をリサーチしている。そこでは追いやられた人々の失われた宗教や生活様式、過疎化していく地方都市の現実や、気候的に共通する「北国」の人々と自然とのかかわり方など、様々な共通点が見出された。家族と自らのアイデンティティという個人的な関心が突き詰められた先には、失われゆく文化や時代の流れの中で廃れゆく共同体の現実が普遍的な問題として立ち上がってきた。

そうした関心のもと、今回の滞在制作では同じ東北地方の青森で、過去から今に続く何かを探すことから制作が始まった。様々な民俗資料に当たっていく中で、千葉は裂織に行きついた。裂織は布が貴重だった時代、裂いた古くなった布や布くず、植物の繊維などを麻糸などと一緒に織り込んだ布である。寒冷地である東北地方にその起源を認められるが、北前船とともに近畿から東北に類した技法が広がった。青森ではサグリと呼ばれ、生地が厚く水に強いそれらは漁師の仕事着として沿岸部で多く使われたという[1]。また千葉の出身地である岩手と文化的にも近い太平洋側の南部地方では、北前船からの木綿糸はあまり手に入らなかったが、鉄道が開通して以来、同じ技法で色鮮やかな多くのこたつ掛けなどが盛んに作られた。千葉の仕事は、青森市が所蔵していたこれらの布と対峙するところから始まった。

これらの資料は、実際に使われていたものであり、丹念に見て行くと利き肩に何かが擦れたような跡があったり、裏布に当時の生活を偲ばせる手近な素材が使用されていたりするなど、着衣していた漁師たちやそれらこたつ掛けを使用していた人々の動きや暮らしを想像させるような痕跡がそこここに残っている。千葉はそれらをピンホールカメラによって撮影したのだが、露光時間のかかるこの技法の採用は、まるでじっくりと見つめる眼差しごと捉えるかのように、今そこに残っているモノの奥に見え隠れする過去を定着させようとする。さらに千葉はそれら資料と資料が収集された場所の風景を同じピンホールカメラで多重露光によって重ねることで作品としてのイメージを作り出していった。

千葉がピンホールカメラを使った作品を初めて発表したのは、2014年に開催された「アート@つちざわ<土澤>」展においてである。千葉はこの時千葉と同じく東和町出身の画家萬鉄五郎へのオマージュ作品として、萬が100年前に撮影したという写真と現在の土沢の風景を自作のピンホールカメラで多重露光撮影した作品を制作している。同じ場所に縁をもつ二人の作家がみた東和町の風景を、100年という年月を越えて結びつけようとした際に用いられたのが、ピンホールカメラによる多重露光であった。そして今回も今ここにある過去の痕跡を残す布と、もはやそれら資料の記憶も継承もなく、だがそれらが使用された時と同じようにただそこにあり続ける土地の風景を重ねることで過去と現在という断絶された時間をつなぎ合わせるようにイメージが作られていった。

それぞれの作品は、それぞれの個別のタイトルが示す通り場所の景色と資料が重ねられているが、固有の事物と判別できるものもあれば、現実の事物というよりは何者かの亡霊のようにぼんやりと光のグラデーションの中に溶けている像もある。確かに撮影されたイメージは具体的かつ象徴的な対象が写され、イメージが作られているのだが、千葉がここで現そうとしたものはその具体的なイメージの組み合わせのみならず、むしろそれぞれの事物や場所が発するエネルギーのようなものが混じりあって生まれる層なのではないだろうか。

実際に今回の展示において千葉はこれらピンホールカメラで撮影したネガから大判ラムダプリントを作る際に、ピンホール写真の特徴でもある淡い光のグラデーションや繊細なフレアを強く意識していた。最終的に出来上がった作品は、豊かな闇と消え入りそうな細やかな光の差異を丁寧に捉えており、その繊細な層が《時の層》という作品を、単に過去と現在の事物を重ねて露光しただけではなく、被写体から沸き立つみえない時間のエネルギーの層を捉え、より複雑な層の存在を現す作品に仕立てていた。

過疎化していく地域は滅びゆく運命にあるのは間違いない。それは残酷で不可逆的な時の流れだ。しかし千葉はそれら去りゆくものをあきらめず、丹念に拾い集め、執拗に留めようとする。

今回リサーチの中で千葉は「南部裂織保存会」と出会った。そこでは1970年代にほとんど失われかけていた技を探り出し、その技を継承しようとする人々の集まりであった。現在は地域の特産物として注目されているこれらの技はこうした人々の意志と継続的な活動、そしてそのことに対する誇りと喜びがなければ、継承されていなかった。現在作られている布は、貧しかった当時の人々の必要が生んだ背景とは異なるが、姿と目的を変えたとしても同じように作る喜びをその根底につなげながら続けられている。千葉はそのことに共感し、映像作品として《裂織、生まれ変わる布の命》を制作した。それは時代時代に対応し、消えゆく過去を現在の在り様で目的や瑣事を変化させながらもある種の精神性を引き継ぎながら後世に伝えていく人々の姿であり、そこには千葉の制作における根本的な欲望に通底する意識をみることができる。

岩手に生まれ、現在山形で生活をする千葉は東北という土地をみつめ、失われゆくものの現在ある最後の痕跡が放つ光を捉えようとする。個人的な問題意識から発したこの試みは、今人間の文化の変化と衰微それ自体をみつめている。

[1] 『裂織―サグリとコタツがけ―』青森市歴史民俗展示館「稽古館」、飯田美苗監修、2003年。

「石と語る」(《父の家》より)

和紙にサイアノタイププリント

「行き来る」(《父の家》より)

和紙にサイアノタイププリント

「1915年のよ志夫人、土沢で」

(《新しき原始のとき――鉄人・萬鉄五郎へのオマージュ――》より)

ピンホールカメラによる撮影

インクジェットプリント

《光とサグリ、深浦町》

ラムダプリント

《廃船、外ヶ浜町》

ラムダプリント

《奥州街道にて》

ラムダプリント

《外ヶ浜町のホタテと漁師》

ラムダプリント

Ubiquitous Views

10:00am-6:00pm, July 30 — September 11, 2016/ admission free

CHIBA Naoko

千葉奈穂子

"Layers of Time"

Photographs,2016

photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

Capturing Layers of Light

KONDO Yuki

Taking photographs for cyanotype print, one of the old techniques of photography, CHIBA Naoko uses handmade Japanese paper. In cyanotype print, images appear in many shades of blue, and since handmade Japanese paper has a unique uneven surface depending on the length of plant fiber unlike machine-made paper, a photograph printed in cyanotype looks blue and a little blurred, forming a mixture of clear and unclear images. The texture looks like a painting rather than a photograph, as well as scenery of an uncertain past rather than contemporary scenery. Or it looks like a timeless scene in one’s partly blurred memory. The photographed subject, however, is the very scenery that exists here and now.

CHIBA Naoko has been taking pictures since 1997 of a farmhouse on her father’s side, which has a 200-year-old main building and the surrounding area in Towa-cho, Hanamaki City, Iwate Prefecture. This seemingly peaceful place has been protected and cultivated by her distant ancestors who maintained the land and the blood for 400 years. In the Japanese Tohoku (northeastern) Region where the legend of Ezo [1] people’s leader Aterui and Ainu [2] words still remain, cold weather damaged crops and famine hit time after time, activities of people living with nature as well as history of life and death are accumulated, which cannot be simply brushed off by saying ‘weight of time.’ Such land, however, has forgotten layers of the past as the times change, and physical things that have barely conveyed past lives are going to disappear.

Chiba’s Father’s House, which could be considered her lifework, is a series of photographs capturing such land and what has been left there. Trying to find out her identity, she exposed and fixed onto film her relations’ signs in the region including ambiguity of fading memories of people and the society in the historical flow of modernization. And at the root of her works is her interest in recording what keeps going on faintly from the disappearing past to the present, together with the whole atmosphere surrounding them, by the use of ‘photography,’ a means of expression and a recording medium.

It seems a natural consequence that this production, which began with searching for her family’s history, gradually developed to an exploration of the old stratum of land called Tohoku. In the project “To the north of the spirit” in which Chiba has participated since 2014, she carries out research in culture and life of people living in the north, while making residency works in Fukushima with artists from northern cities in Europe. There she found various similarities:―lost religion and lifestyle of expelled people, the reality of depopulating regional cities, and how people of northern regions sharing a common climate interact with nature. Probing into her personal interest in her family and self-identity, she has found that lost cultures and the reality of communities declining with the times come up as universal issues.

Developing such an interest, she started her production with the search for something that continues from the past to the present in Aomori in the same Tohoku Region. While dealing with various folkloric materials, Chiba came on ‘sakiori’ cloth. In the times when any cloth was valuable, old torn fabric, scrap cloth, plant fiber, etc. were woven together with hemp yarn to make cloth. Its origin is known to be in the Tohoku Region which is a cold district, and similar techniques spread from the Kinki to the Tohoku Region with kitamae-bune (a merchant ship that carried goods on the Japan Sea route). The cloth was called saguri in Aomori, and as the fabric was thick and resistant to water, it was popular for work clothing for fishermen in the coastal area. [3] In the southern region of Aomori on the Pacific side, which is culturally close to Iwate where Chiba is from, much cotton thread was not obtainable from kitamae-bune, but after the railroad opened, many kotatsu-gake (a coverlet for a kotatsu) were made using the same technique and colorful cloths. Chiba started her research by dealing with these cloths of Aomori City’s collection.

These materials were for daily use. When they are closely observed, it is noticeable that the shoulder part of the dominant arm is worn thin, or handy materials in daily life at the time were used for lining. Since those traces remain here and there, we can imagine movements and lifestyle of fishermen who wore such clothes and those who used the kotatsu-gake. Chiba took pictures of them using a pinhole camera. Adopting this technique, which consumes exposure time, it seems that she tries to capture even her intense eyeing in order to fix the past appearing and disappearing in the back of what remains there. Moreover, by overlapping pictures of these materials and the scenery of the place where they were collected in multiple exposure using the same pinhole camera, she created images as a work.

Chiba first showed her work using a pinhole camera at Art@Tsuchizawa in 2014. To pay homage to YOROZU Tetsugoro, painter who was from the same hometown Towacho as Chiba, she made a work by photographing a picture that Yorozu took 100 years ago and the scenery of Tsuchizawa at present in multiple exposure using her self-made pinhole camera. The scenes of Towacho observed by the two artists, who have their roots in the same place, were linked beyond 100 years by using multiple exposure of a pinhole camera. And again in this project, she created images so as to link severed time between the past and the present by overlapping the cloths which have traces of the past and the scenery that simply remains there, with neither memory nor succession of materials, as it used to be when the cloths were used.

In each of her works, as their respective titles indicate, the scenery of places overlaps the materials. While some of them can be identified as specific objects, others look vaguely melting in the gradation of light like some ghosts rather than real things. The photographed images actually show tangible and symbolic objects to make up the images, but what Chiba is trying to express here seems not to be just a combination of tangible images. She probably intended to reveal layers developed with mixtures of sorts of energy emerging from each object and place.

When making large-sized Lambda prints from negatives made with a pinhole camera for this exhibition, she was strongly aware of gradations of pale light and subtle flare, which are features of pinhole photography. In the finished works, the difference between rich darkness and disappearing delicate light is carefully captured, and with such subtle layers, Layers of Time has become a work which not only represents overlapped and exposed past and current things but also reveals the presence of more complex layers capturing invisible energy of time bubbling up from the subjects.

There is no doubt that a depopulated area is destined to disappear. It is due to a cruel and irreversible flow of time. Chiba does not give up, however, those which are going away, pick them up with patient care, and tries to keep them persistently.

During the research, Chiba encountered the Nanbu Sakiori Preservation Society. It is a group of people who find out techniques that were almost lost in the 1970s to inherit them. But for these people’s wills, continuous activities and their pride and joy in them, these techniques that are currently drawing attention as local specialty would not have been inherited. The cloths made at present have the background different from those days when poor people made them out of necessity. Even if the form and purpose changed, however, the cloths are being made based on the same joy of making them. Feeling empathy for this, Chiba made a video work Sakiori, The Many lives of Fabric. It shows people who pass on the disappearing past to future generations while changing purposes and trifles to suit the present and yet carrying on a kind of spirituality. There, you can see in their awareness a commonality underlying Chiba’s fundamental desire in her production.

Born in Iwate and living in Yamagata, Chiba keeps her eyes fixed on the land of Tohoku, and tries to capture lights emitted from the last existing traces of disappearing things. This attempt emanated from her personal matter of concern is now gazing into change and decline in human culture.

[1] Ezo, also called Emishi, are people who lived north of the Kanto Region from the ancient times, and were insubordinate resisting the rule of Yamato imperial court.

[2] Ainu are indigenous people who lived in a wide area ranging from the northern Tohoku region to Sakhalin and the Kuril islands.

[3] Sakiori—saguri and kotatsu-gake, the Keiko Kan Folk Heritage Museum of Aomori City, supervised by IIDA Minae, 2003.

"The stone said"

(from the series of Father’s House),

cyanotype on Kurotani paper,

55.5cm×55.5cm, 2011.

"Going and Coming"

(from the series of Father’s House),

cyanotype on Kurotani paper,

56.0cm×56.0cm, 2011.

"Mrs. Yorozu, in 1915, at Tsuchizawa"

(from the series of The beginning of a new primitive era -- A Homage to Yorozu Tetsugoro--),

pinhole photographs,

inkjet print, 2014.

"Gleams in the Saguri work clothes,

in Fukaura town"

Lambda print

"Hulks,in Sotogahama town"

Lambda print

"In Oshu Kaido"

Lambda print

"Scallops and a fisherman

in Sotogahama town"

Lambda print