“Re-Modernologio” phase2 :Observation and Notation

October 23 (Sun) ~ December 18 (Sun), 2011 10:00 - 18:00 / Free

NIWA Yoshinori

Putting Stones collected in the bottom of sea on the top Mt.Hakkoda

Body Plunging - Comical Behaviors to Puncture Society

HATTORI Hiroyuki

Yoshinori Niwa is eye-catching — a slightly hunched, lean body, with a rich beard connected to sideburns, tottering along wearing a red beret and a backpack,. His appearance has a magical charm that attracts people, probably due to his nature as a performer.

Niwa taps into different places with only the clothes on his back, and calmly carries out things, requiring no special ability, that anyone can do but no one has ever tried. The origin of his practice dates back to his high school days, during which a noise music band he formed with friend released a CD from a Czech label. He was precocious enough to be deep into noise music, and since then, his attitude has been consistent throughout his oeuvre. Although it was his inability to play any instrument that drew him into noise music, the artist was gradually attracted by the minor genre’s underground scene formed of a small population of strongly connected noise lovers worldwide. Subsequently, he came to know that the noise scene was related to the current avant-garde fine art practices descended from Fluxus and the like, and this then made him determined to do art himself. Another inspiration came from his uncle, who had had links with “Zero Jigen” (Zero Dimension), a Japanese performance group quite active around Nagoya in the '60s, known for their all-nude rituals. Through episodes the uncle had told him about, Niwa was introduced to the art world from another angle. To him, art seemed like a world where various activities ungraspable yet exciting were happening. Given these background stories, there is no wonder that Niwa's performances are full of essences of happenings and events in the '60s and '70s.

Basically, his performances are presented mainly in the form of video documentation. Although the word "performance" usually reminds us of actions carried out in front of people in public, Niwa's work is often done only with his own body and a video camera, without being directly seen by any audience. His actions include sucking up muddy water from a puddle on the street and spitting it out into another puddle at a different location, using his mouth as a container [fig. 1]; taking a plastic bag full of combustible waste collected at his home in Tokyo, to San Francisco, and throwing it away at a local garbage dump; and bringing a magazine he bought at a kiosk to other kiosks to purchase the same item many times. Such actions, carried out with no exaggerated gestures, are recorded with a video camera, so their processes and end results are conveyed to viewers through resultant videos. No special abilities or techniques are required to suck up and spit out water, to throw away waste, or to purchase commercially supplied products. They are mundane acts that everyone does in their everyday life, but the artist does them in atypical situations, where there is no reason, in the usual sense, to do them. This unreasonability is what Niwa focuses on. For example, we are supposed to throw away garbage at a designated nearby dumping point. Without questioning, we separate garbage into the combustible and the noncombustible, and dump them on fixed days at a fixed place. We do not have to pay attention to how the garbage will finally be disposed. In the world today, where everything is put in order in an economic and systematic way, we can ignore so many things, without giving them any thought. Niwa's act of going to San Francisco to dump his home garbage is an action questioning such fixed, conventional systems in society. In principle, you are the legitimate owner of your garbage, until it is thrown away at a disposal point. And, you can go through customs if your belongings are not considered dangerous goods, even if they are in a plastic bag. Thus, Niwa could take it overseas, and the garbage went to a disposal site in San Francisco. Things become garbage only when they are dumped. Then, is it a problematic act to get rid of his garbage in San Francisco? Things in his plastic bag had been produced somewhere in the world, whereabouts we never know, and had ended up in his place in Tokyo. There is no clear answer to the question. From one perspective, it may be problematic behavior, and from another, merely a playful joke.

The work titled “Purchasing My Own Belongings Again in Downtown” (2011) shows Niwa taking a magazine that he had purchased at a kiosk to other kiosks and bookshops only to purchase the same thing again. Is this, in fact, a criminal act? Shoplifting, of course, is clearly defined as so, but I guess there is no law referring to this act of multi-purchase. Needless to say, Niwa himself does not acquire any profit from this. Rather, moneywise, he makes a loss. It seems that a product regulated with a barcode is re-purchasable as many times as you want, if the shop handles it. Niwa's action brings confusion to the balance calculation of the shop, making extra profit as a matter of fact. Is this a criminal act? There should be no rule that judges this, which clashes with today's capitalist society that chases only after profits. Like this, with his incredible actions, Niwa neither confirms nor denies, but questions socially constructed systems. Putting into practice acts, which are not quite able to be judged in today's society, and creating tense moments, he attempts to leap from the everyday.

Niwa's actions are often prescribed by the work's title. In reference to “Go to San Francisco to throw away the garbage of my house” (2006) and “Purchasing My Own Belongings Again in Downtown,” among others, it can be said that acts indicated by his titles can often be reduced to "putting A in the state of B." Sentence structures in his titles are very important, since he carries out the act literally as described. Substituting "A" and "B" with two things that usually cannot be juxtaposed with each other, Niwa sheds light on mysterious systems in society that have been automatically constructed without our awareness.

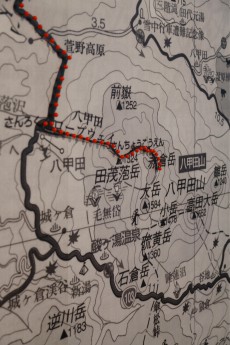

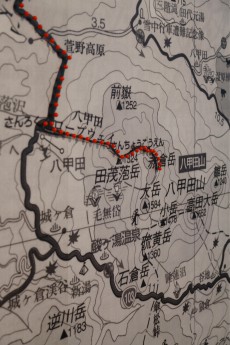

In Aomori, he spent three months creating a work called “Putting Stones collected in the bottom of sea on the top of Mt. Hakkoda” (2011). As the title states, the work shows how he collects stones on the seabed of Mutsu Bay, Aomori, takes them to the top of Mt. Hakkoda, and stacks them there, to make the mountain a bit higher. He first spent a week with his assistant, diving with a wet suit into the cold seawater in October, to collect dozens of kilos of stones that had become rounded over a long period of time. Put into backpacks and soil sacks, those stones were taken to the mountaintop. This whole process is shown in the video. Niwa stacked stones to the height of approximately 60 cm, just like another small mountain. He then brought the stones back to ground level. He repeated this whole process many times. Basically, you have to take home what you have brought to the mountain, because the area around Mt. Hakkoda is designated as a national park and managed by the government. That is why Niwa was carrying as many stones as possible, making a small mountain on the top, and then taking the trouble of bringing them back all the way down. What does this action bring into relief? Of course, the act itself has no effect. A long time ago, the mountain was just a mountain in terms of landform, but it has become a national park, a possession of the country, where the rules set to protect its environment are thus applied. In the name of protecting the nature and native vegetation of Mt. Hakkoda, you are required to take home everything you have brought from the outside world. There is a possibility that the stones that Niwa carried used to form the mountaintop in ancient times, and then rolled down to the bottom of the sea. Even so, today, they belong to the area outside of the national park, so their abandonment inside the area is prohibited. By silently and repeatedly stacking stones, Niwa questions this rule regarding what belongs to what, and who owns what. Again, he neither confirms nor denies the rule. Viewing with a keen eye, he discovers invisible laws that the society has set without our consent and that we blindly follow, and makes them visible to other people through his work.

Moreover, somewhere in the depths of his work, there is humor that evokes laughter. While he quietly carries out his actions, various people come to him. When he was picking up stones in the bay, an elderly man approached and spoke to him about the original greatness of mother nature, insisting that it had been destroyed and would not recover unless human beings became extinct. On the ropeway platform, a staff member, suspicious of the artist with such enormous baggage, came to caution him, but did not stop him. In the process of this work, there were so many intriguing encounters and conversations [fig. 5]. Niwa was just quietly carrying stones. However, probably partly due to his charm, people were drawn to talk to him. The conversations between the artist and others contain some issues to do with belongings and ownership. The park employee told Niwa the national park rules, with no offense. They are implicit rules that he usually does not have to verbalize. His explanation illuminates contradictions and problems about definitions of "ownership," as well as things supposed to be "public," in this society. We are then naturally prompted to reconsider the way we live, and made aware of how blind we are to the systems around us.

Nevertheless, the most attractive element of his work, in fact, is the artist himself. Many works that deal with systems in society or publicness tend to be overly serious, with no humor, however due to his uniquely charming appearance and comical behavior, this tendency is not applicable in his case. Niwa plunges his own body directly into serious or cynical situations, evoking quiet laughter with his unique presence. In such a manner, the artist presents his fundamental "discomfort" toward our lifestyle based on consumption. Beyond the laughter, he tries to discover alternative ways of life, and we get hints from his modest pursuits.

Putting Stones collected in the bottom of sea on the top Mt.Hakkoda

Putting Stones collected in the bottom of sea on the top Mt.Hakkoda

Tossing socialists in the air in Romania

Purchasinf My Own Belongings Again in Downtown

「再考現学 / Re-Modernologio」phase2 : 観察術と記譜法

2011年10月23日(日)~12月18日(日) 10:00 - 18:00/無料

丹羽良徳

NIWA Yoshinori

《八甲田山の頂上に海底で拾った石を積む》

突入する身体 〜滑稽な振舞いが社会に風穴をあける

服部浩之

少し猫背でひょろりとした身体にモミアゲまでつながる豊かな髭を蓄え、赤いベレー帽とリュックを身につけてふらふら歩く丹羽良徳の姿はよく目にとまる。その風貌にはパフォーマー独特のなんとなく人の目を惹く不思議な魅力があるのだ。

身ひとつで様々な場所に飛び込み、特別な能力がなくてもできるけれども決して誰もやらないようなことを淡々とやってのけるその活動の原点は、高校時代まで遡る。丹羽は高校時代に同級生と組んでいたノイズバンドでチェコのレーベルからCDをリリースしている。高校生でノイズに行き着くこと自体早熟感が漂うが、当時から彼の姿勢はわりと一貫している。楽器が弾けなかったことから至ったノイズの世界だそうだが、彼が興味を持ちのめり込んだのは、ノイズというそもそも活動人口が少ないマイナーな分野では世界中の類似の嗜好を持つ人たちが密接につながっており、深淵なアンダーグラウンドなシーンが形成されているという状況だった。そういうシーンは、フルクサス[i]などの流れを汲む前衛的なファインアートにも深く関わっていることを知り、そこからファインアートをやろうと決意したと言う。同時に彼の叔父が60年代に名古屋を中心に各地で裸体の集団でのパフォーマンスを繰り広げていた〈ゼロ次元〉[ii]に関わっていたことから、その話を聞き、なんだか分からないがすごいことが繰り広げられている世界の存在を別の方向からも知るようになったと言う。その流れを理解すると、丹羽のパフォーマンスに60~70年代を彷彿とさせるハプニングやイヴェント的な要素が充満しているのが、自然に受け入れられるだろう。

彼のパフォーマンスは基本的にビデオによるドキュメントを中心に提示される。通常パフォーマンスというと公衆の面前で繰り広げられるものが想起されるが、丹羽のそれは人知れず彼の頼りない身体とビデオカメラのみで推進されることが多い。街中の水たまりの水を口で吸い上げて、離れた場所の別の水たまりに口移しで泥水を運んだり、東京の自宅の可燃ゴミの入った袋を、サンフランシスコまで持って行ってその街のゴミ捨て場に捨てたり、あるいはあるキオスクで購入した雑誌を別のキオスクに持っていきそこで再びそれを購入するということを何度も繰り返したりする。作品では彼が淡々とその行為を実行する様子をビデオに収めて、その過程と顛末を映像として公開するのだ。水を吸って吐いたり、ゴミを捨てたり、ものを購入したりとどれも特別な技術や能力は必要としないし、その行為自体は誰でも日常的に行っていることだ。ただ、彼はそれを特殊な状況下で実施するのだ。普通に考えたらなぜそんなことをするのか理解に苦しむような状況ばかりだろう。丹羽はまさに、この私たちが理解に苦しむという点に着目している。例えば、自宅のゴミは家のそばの所定のゴミ捨て場に捨てるのが当たり前だ。なんの疑いもなく私たちは、燃えるゴミや燃えないゴミなどに分別し、決められた日に決められた場所に捨てる。そして最終的にそのゴミがどういうかたち処分されるかはほとんど意識することなく生きている。とても合理的でシステマチックな現在の世界では、深く考えなくてもやり過ごせることは非常に多い。丹羽が自宅のゴミをサンフランシスコまで捨てにいくことは、そういう社会の当たり前のシステムに疑問を呈するアクションでもあるのだ。ゴミはそれをゴミ捨て場に捨てるまでは、その人の正統な所有物である。丹羽がゴミ袋に入れて持ち運ぶものは彼の所有物で、危険物とされなければ税関では止められず、海外まで持ち出せてしまう。そしてそれはサンフランシスコのゴミ処理場に捨てられた。その瞬間にこれはゴミになる。そもそもこの世界のどこで生産されたかも不明な東京の丹羽のもとに集まったこれらのゴミをサンフランシスコで捨てることは問題のある行為なのだろうか?そこに明確な解はない。ある視点からは問題行動とされるかもしれないし、別の視点からは単なる戯れととられるかもしれない。

また、《自分の所有物をまちで購入する》というタイトルが付された作品は、彼があるキオスクで買った雑誌を別のキオスクや書店に持って行き、それをもう一度購入する様子捉えたものだ。これは果たして犯罪なのだろうか?万引きは明確な犯罪として規定されているが、おそらくこういう多重購入に言及する法などないだろう。当たり前だが、丹羽自身はそれにより利益を得ることはない。それどころか金銭的には不利益さえある。バーコードで管理された商品は、その取り扱いがある店ならばどこでも何度でも購入できてしまうようだ。この行為により店側は収支の計算は合わないが、貨幣の出入りで考えたら余剰の利益を得ることになる。これは犯罪なのだろうか。現在の資本主義社会における利益の追求とは矛盾するこの行為の善悪を判断するルールは存在しないだろう。このように丹羽は社会がつくりだしたシステムを否定も肯定もせず、ただそのありえないアクションによって疑問を投げかけるのだ。今の社会において善悪の判定が不可能なギリギリの行為を実践し、緊張の一瞬を生むことで日常のなんでもない状況から飛躍しようとするのだ。

丹羽の行為はそのタイトルに多くを規定される。前述した《自宅のゴミをサンフランシスコのゴミ捨て場に捨てにいく》、《自分の所有物をまちで購入する》などを参照すると、「AをBの状態にする」という手法でタイトルが付されている。彼はタイトル通りの行為を実践する過程を作品とするため、タイトルは非常に重要だ。「A」と「B」に通常は絶対に併存することがありえない事象を代入しぶつけることで、私達がおよそ気付きもしない自動的につくられた不思議な社会のシステムを浮き立たせるのだ。

青森では《八甲田山の頂上に海底で拾った石を積む》という作品を約3ヶ月かけて制作した。タイトル通り、陸奥湾で拾った石を八甲田山の頂上まで運び、それを積んで山頂を少しだけ高くしようとする過程を記録したものだ。丹羽はアシスタントとともに約1週間かけて、10月の冷たい海にウェットスーツを着て潜り、永い年月をかけて丸くなった石を何十キロも拾い集めてリュックサックやドサ袋に入れ、山の頂上まで運んでいき、その姿をビデオで捉える。石を運んではそれを積み上げて60センチ程度の小さな山を山頂に築く。そしてその石をまた持ち帰る。その繰り返しだ。八甲田山一帯は国立公園として国により管理されているため、原則持ち込んだものは全て持ち帰らなければならない。そのため、丹羽は毎回持てる限りの石を持っては八甲田山に登り、小さな山をつくって、またそれを持ち帰るのだ。この行為からなにが見えてくるのだろう。もちろん行為そのものには大した意味はない。山ははるか昔は単なる山以外のなにものでもなかったはずだが、国立公園として保護されたことにより国の所有物となり、国が規定した公園管理のルールが適用される。八甲田山の自然や原生植物を護るなどという理由により外から持ち込んだものは全て持ち帰らなければならない。丹羽が運んだ石は、もしかしたらはるか太古にはこの山頂を形成していて、それが海の底に転がったものかもしれない。しかし現在の管理区域の境界外から持ち込んだものなので、これをそこに留めることはできない。この所有のルールに彼は「石を積む」という無言の行為により疑問を投じるのだ。丹羽はそのルールを否定も肯定もせず、彼が興味を持つ社会が気付かぬうちにつくりだしてしまう暗黙の法のようなものを鋭い観察眼で発見し、作品化を通じて他者にもそれを眼に見えるかたちにするのだ。

また、彼の行為の奥にはどこかで笑いを誘われるユーモアがある。人知れず実践する行為の過程で彼は様々な人に出会う。海で石を拾っているときに、自然の偉大さや、破壊された自然は人間が絶滅するまで戻らないというような主張をする老人があらわれて、丹羽に語ったり、ロープウェー乗り場の職員が大きな荷物をもつ丹羽を怪訝に思い牽制はするが制止はしなかったりと、その過程には不思議な対話がいくつもある。丹羽はただ石を運んでいるだけなのだが、それを見る人になんだか構わずにはいられなくさせるものが彼にはあるのだ。これらの会話からもやはり所有にまつわる様々な問題が透けて見えてくる。ロープウェー乗り場の人は、国立公園としてのルールを悪意などなく彼に伝える。普段は説明する必要もないような暗黙のルールを口にする様子を眺めていると、社会がつくりだした「所有」を規定するものや「公共」とされる事柄に関する様々な矛盾や疑問が見えてくる。それによって私達は無意識に生きている日々を今一度再考するよう自然と促されたりする。

とはいえ、やはり丹羽の活動の最も大きな魅力は彼自身の存在にあるだろう。丹羽はその愛嬌ある独特な風貌や振舞いにより、社会のシステムや公共性の問題に言及するタイプの作品が陥りがちなシリアスだけれどユーモアがないという状態をひょいとすり抜けてしまう。深刻で皮肉な状況にも、彼の身体をもってダイレクトに貫入することで、小さな笑いを誘うのだ。そしてその先には、私達の消費を土台とした生活への根源的な「違和感」の提示と、それとは異なった生活像のささやかな模索への兆しが見えている。

[i] 1961年にジョージ・マチューナスがニューヨークで開催した講演をきっかけに始まった芸術運動。美術、音楽、詩、パフォーマンスなど様々な領域、様々な国のアーティストが流動的に参加し、「イベント」と呼ばれる日常的な行為を主な表現手段とした。

[ii] 1950年代後半から70年にかけて活動したパフォーマンス(ハプニング)集団。主宰は加藤好弘で当時日本各地に300人以上のメンバーがいたとされる。人間の行為を無為=ゼロに導くことを主張し、「儀式」と称するパフォーマンスを街頭で繰り広げた。

《八甲田山の頂上に海底で拾った石を積む》部分

《八甲田山の頂上に海底で拾った石を積む》部分

《ルーマニアで社会主義者を胴上げする》

《自分の所有物を街で購入する》