普遍的な風景

2016年7月30日(土)~9月11日(日)10:00~18:00 会期中無休・入場無料

ヨーグ・オベルグフェル

Jörg OBERGFELL

《小屋》

インスタレーション、2016年

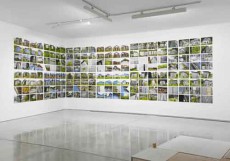

《小屋の類型学》

192枚のインクジェットプリント、各29.7×21cm、2016年

《ステップ》

木材、サイズ可変、2016年

撮影:山本糾

いくつもの距離を持つ小屋

伊藤聡子

ACACの曲線を描くギャラリーを進むと奥の壁の一辺に、《小屋》の小さな入り口がある。それまでの誘導的かつ天井が高く開放的な空間から一変、蛍光灯の光が真っ白な空間を際立たせ、どこか別の街のギャラリーに偶然入ってしまったような印象を与える。

オベルグフェルは、都市や建築物、日々の風景に溶け込んだ人々の生活の中から素材を見つけ、彫刻や映像などを媒体に、自然と都市の関係性、都市生活に潜む社会性をユーモラスに内包する作品を制作する。自身の外側にある物事、世界と対峙するように独自の視点で素材を拾い上げ、主題を直接的に示唆しすぎないような形で人々の前に提示する。その対象と展示方法の選択は、軽やかな距離を保つようである。

《小屋》は、ACAC周辺に点在する小屋のリサーチと撮影から始まった。用途に関わらず日用品を別な物と組み合わせたり、作業がまだ続いているかのように人の手の跡が残っていたりする一方、働く建物として、個人にとって機能的な作りに整えられている。クロード・レヴィ=ストロースは自著で、ありあわせの道具や材料を用いて自分の手でものを作る器用仕事(ブリコラージュ)を神話的思考になぞらえられ、科学的思考と対比する。しかしながら両者は根底で密接につながりを持ち、互いに支えあう関係として並置されると述べている(1)。拾い上げた素材を変化させて組み合わせるオベルグフェルの作品は、小屋が既存の材料を寄せ集めて作られる様子と重なるところがあるだろう。作家は小屋に「混沌と秩序の絶妙なバランス」(2)を見つけ写真で記録し、その「器用仕事」をインスタレーション作品へと展開していった。

《小屋の類型学》は192枚の写真を集めた一つの大きな作品だ。タイトル通りタイポロジーの手法が用いられ、近づいてよく見ると一定方向から撮影した小屋の写真と、その造りを部分的にとらえた写真が規則的に並置されていることに気付かされる。部分写真では、作家自身の視点を用いて様々な材料の寄せ集めがうまく機能していることに焦点をあてているが、タイポロジーの一定のルールの中に組み込むことで、客観性を失わずにその「器用仕事」を提示する。

錆びた鉄のパイプの束が器用にも壁を支えている様子。ペンキが垂れた壁や板の継接ぎが作り出すグラフィカルな構図。これらの一枚ずつで特徴をもつ写真は、作家の視点を追体験させるかのように見る者を惹き付け、日常に隠れてしまった物の形や質感に目を向けさせる。そうかと思えば、密集しているため隣同士の写真は見る者の目に入り込み、写真群が一つの作品であることに再び目を戻させる。見る者は焦点を一枚の写真に合わせられながら、引いては全体を一つの大きな写真または壁紙のように見る。距離感の違いを起こすようだ。

そういった距離感が別の形で《ステップ》と《壁》にも現れる。これらは小屋の一部を取り上げた作品であるが、とはいえそれぞれが空間を形成する機能そのものと化している。観客は《ステップ》を踏まずして展示室の中に入れないし、《壁》もその一角を担い従順にも自らの役割を果たす。空間の中に姿を隠した「作品」はしかし、不明瞭なものに対する距離を見る者との合間に保ちながらも、その違和感はかえって人を惹きつける。そしてその異物は実際に周辺に点在している小屋の一部を示すものなのだと気づかせると、作品としての認識の変化と親近感をもって一気に距離を縮めてみせる。

いわゆるホワイトキューブ自体は、それまでの空間との差を示すとともに、日常的用途のために無作為に現れた手の跡を、均一化された様式の中に浮かび上がらせる。けれども《ステップ》や《壁》のように機能に徹することで空間に溶け込もうとする作品では、単に無機質な白い空間にその対象の特徴を描き出すだけでなく、インスタレーションにおける物体と空間がどちらも出過ぎないようなバランスが保たれる。この空間は作家自ら白いペンキで塗り入念に設えられたが、作品を置くための様式というより、作品を左右し得るため丹念に作られるキャンバスの下地のようであり、この作品の重要な土台となった。

《壁》で用いられた小屋作りの定番ともいえる波板の半透明のプラスチックは、奥に置かれた雑多な作業具を透かせて見せ、内と外を反転させるようだ(fig.1)。まるで小屋の一部を持ち込むようにその器用仕事を模しながら、ホワイトキューブの一片を切り取ってそこに組み合わせたようでもある。それはオベルグフェルが用いる作風と、器用仕事の方法とを重ねてみることもできる。閉じられた展示空間に与えられた隙間は、ギャラリーの外へとつながる。

オベルグフェルはしばしば物と物の組み合わせに対比関係を示す。例えばACACの池の中に設置された《置換》では、実際にある小屋を半分に切り、その上下半分ずつを新しい素材と取り替えることで、もとのトタンや板の継接ぎの様子を強調させてみせる。またその小さな小屋は、真夏の森の風景に溶け込みながらも、ACACの均衡のとれた建築の真ん中、池の中で居心地を悪そうにしているのだった。

対比させる物の関係をどのくらい離すのか近づけるのか、そのさじ加減で表現は変わってくる。このインスタレーションの中では、随所でこういった関係性が多彩に現れていた。それらは見る者を惹きつけ、中に潜んでいるユーモアを発見させる。

奥の壁にもう片方の《置換》の小屋を撮影した一枚のモノクロ写真が掛けられている。ある林の中に佇むその一軒の小屋の写真は、《小屋の類型学》のインクジェットプリントとは大きく趣を変え、古い肖像写真のようだ。感じさせる古さは記憶、またはストーリーを思わせ、見る者の想像はその写された場所へとつなげられる。それが「いつ/どこなのか」というより、「実際にどこかにあった/あるらしい」という見えない存在に、さらに想像が広げられる。展示は終了しても小屋はその役目を終えるまでそこに在り続けるのだが、その在り方は、時間を超えて人々の中に残されていく言い伝えのようでもある。見る者の記憶や想像は、また小屋のように継接ぎとなって作品の一部となる。

《小屋》を構成するそれぞれの作品は、小屋の器用仕事を切り取り変化させながらも一つの空間に集約される。見る者と作品、作品と空間、また物と物との間に作家の目で測られた距離を保つ。そしてホワイトキューブから池へ、見る者の想像の線を描きながらさらに遠くへ、軽やかに広がっていくのだ。

(1)クロード・レヴィ=ストロース『野生の思考』大橋保夫訳、みすず書房、1976年。

(2)オベルグフェルが展覧会鑑賞者用の解説に寄せた文章より。

fig.1

《壁》(部分)

fig.1

《壁》(部分)

《小屋の類型学》(部分)

《置換》

《置換》

Ubiquitous Views

10:00am-6:00pm, July 30 — September 11, 2016/ admission free

Jörg OBERGFELL

ヨーグ・オベルグフェル

"Koya"

Installation,2016

"Shed Typology"

192 inkjet prints,each 29.7×21cm,2016

"Step"

Wood,variable dimensions,2016

photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

Koya with different distances

ITO Satoko

As you walk along the curved gallery of ACAC, you come to a small entrance of a ‘shed’ on one side of the back wall. At the scene completely changing from the open space with a high ceiling seemingly guiding you so far, a sheer white space lit up with fluorescent lights is striking enough to impress you that you are accidentally entering an art gallery in another town.

Jörg OBERGFELL finds materials in cities, architecture and people’s lives blended into daily scenery, and using medium such as sculpture, photography and video, he creates works that humorously involve the relationship between nature and city as well as social aspects hidden in urban life. Picking up materials with his own perspective to confront the world and things outside himself, he presents the subject in a way that he does not directly suggest it. His way of selecting objects and installing an exhibition seems to reflect a light distant feeling.

His work on Koya began with research and taking photographs of sheds around ACAC. While in the shed are daily necessities combined with different things regardless of their uses, and traces of people’s hands remain as if their work were still going on, the shed is functionally organized for an individual as a working building. In his book “La pensée sauvage,” Claude LÉVI-STRAUSS describes Bricolage as a form of working with readily available tools. He compares this approach to mythical thinking in contrast to scientific thinking. The two are closely related at the bottom, however, and are juxtaposed as a mutually supporting relationship.[1] Obergfell’s works, in which gathered materials are changed and put together, seem to overlap with the shed, which is made by collecting existing materials. The artist found “an amazing balance between chaos and order”[2] in the sheds, recorded them by taking photographs, and developed such bricolage to an installation work.

Shed Typology is a large piece of work, consisting of 192 photographs. As the title suggests, a method of typology is adopted, and the viewer, when approaching and looking closely, will notice that the photographs of the sheds are taken from specific angles, and photographs partially capturing the construction are juxtaposed regularly. While partial photos focus on how a mixture of various materials functions well from the artist’s point of view, they are incorporated into certain typological rules, and bricolage is presented without losing objectivity.

Shown are, for example, how a bundle of rust steel pipes supports the wall efficiently, and graphical compositions created by walls with dripping paint and joints of boards. Photographs with their respective features attract the viewer through a vicarious feeling of the artist’s viewpoint, and make the viewer become aware of shapes and textures of things hidden in daily life. At the same time, as the photographs are so crowded, neighboring photographs captivate the viewer’s attention, and the viewer realizes again that the group of works makes up one piece of work. If one focuses on from the single picture to the bigger outline, the whole work looks like a huge photo or wallpaper. It seems to cause differences in a sense of distance.

Such a sense of distance also appears in Step and Wall in different forms. While they are works showing a part of the sheds, each of them has turned into a function itself for forming a space. The visitor cannot go into the exhibit room without stepping on Step, and Wall also holds its position to play its role obediently. The work hidden in the space, however, rather attracts the viewer because of its incongruity, while maintaining a distance from the viewer as something indistinctive. And when noticing that this strange thing is a part of the sheds found in the area, the viewer begins to perceive that they make up the work and suddenly the distance is reduced with a feeling of familiarity.

The so-called white cube presents itself in contrast to the previous space, and makes traces of hands unintentionally left in daily use emerge in the homogenized space. However, the works such as Step and Wall, which seem to blend into the space by remaining strictly functional, not only depict the features of the object in the inorganic white space, but also keep a balance between the object and the space in the installation so that neither of them stands out. This space was painted white by the artist himself and prepared with care. Rather than a style in which a work is placed, it is more like a canvas made carefully as it affects the work, and it actually became an important foundation for the work.

Translucent corrugated plastic sheets used in the Wall, which are usual materials for building a shed, show through miscellaneous working tools behind them, and it seems to reverse the inside and the outside. Imitating bricolage, as if parts of a shed were brought in as they were, the artist seems to have cut out a part of the white cube and combined it with the elements of the shed together. You can see Obergfell’s style and the method of bricolage overlapping. A gap created in the closed exhibition space is connected to the outside of the gallery.

Obergfell often shows contrasting relationships in combining objects. In Replacement installed in a pond at ACAC, for example, he cut an actual shed in half, and by replacing the upper and lower halves with new materials, he accentuated the way how the joined parts of the original tin-plates and boards looked. While the little shed blends into mid-summer scenery in the woods, it looks awkward in the pond in the middle of the well-balanced construction of ACAC.

Expressions will change through slightly different distances in the relationship between the contrasted objects, whether it is distant or close. In this installation, such relationships came into sight in diversified ways everywhere. They attract the viewer, and make them discover humor lurking inside.

On the back wall of the gallery, a monochrome photograph of the other half of Replacement is displayed. The photograph looks like an old portrait with the mood totally different from inkjet prints of Shed Typology. The oldness that the viewer feels reminds them of a memory or story, and the viewer’s imagination is linked with the place where the picture was taken. The imagination develops further, from “when and where” to an invisible existence “that was actually somewhere / seems to be somewhere.” After the exhibition is over, the shed continues to exist there until its role is fulfilled, but its way of existence is like a legend that is left on people’s mind over time. The viewer’s memory and imagination will become a part of the work as patches like those shown in the shed.

Each work that consists of Koya is put all together in a single space while cutting off and changing the elements of the shed’s bricolage. The distance measured by the artist’s eyes is kept between the viewer and the work, the work and the space, and objects and objects—drawing an imaginary line that lightly extends from the white cube to the pond, and farther.

[1] Claude LÉVI-STRAUSS, La Pensée sauvage, (Yasei no shiko / The Savage Mind) trans. OHASHI Yasuo, (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, 1976)

[2] Quoted from Obergfell’s text written for visitors to the exhibition.

fig.1

Wall (detail)

"Shed Typology"(detail)

"Replacement"

"Replacement"