TOKOLO Asao × Aomori City Archives Exhibition “Individual and Group”

Individual and Group is the fourth installment in a series of annual exhibitions in which artists use folk items and resources from the Aomori City Archives to interpret the history of the region from a number of perspectives. In this year’s exhibition, the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre invites artist TOKOLO Asao as guest director to shed light on the concept of “patterns.”*1

A trained architect, TOKOLO Asao’s current artwork is rooted in mathematical principles and encompasses various mediums that include architecture, sculpture, and fashion. The word “group,” as seen in the exhibition title, can refer to the mathematical term for a set based on certain definitions and laws; however, it is also a concept that has practical relevance in our daily lives. In the case of Aomori, this is embodied by kogin 2, which is characterized by its odd-numbered stitching. Sewing on the first, third, and fifth vertical threads produces an aesthetically pleasing pattern. By utilizing a simple mathematical principle in this way, individual components interact as part of a larger group, causing intricate patterns to emerge.

The exhibition showcases a combination of patterns created solely by TOKOLO Asao and those made in collaboration with others. Additionally, it presents symbols of magical and ritual significance like those found in Ainu artifacts; practical and ornamental patterns like those found in kogin; patterns in nature like those seen in Aomori’s nishiki-ishi jasper stones; and various patterns of materials found inside the Aomori City Archives. We invite you to experience and enjoy the concepts of individual and group through patterns that have arisen from Aomori’s natural landscapes alongside those born of a collaboration between the Aomori City Archives and TOKOLO Asao’s creative mind and artistic eye.

*1 The word “pattern” here refers to both designs and images.

*2 Kogin is a type of work garment or embroidered fabric made from linen with cotton thread embroidery used for insulation or garment reinforcement in the Tsugaru region of western Aomori.

—

Exhibition view

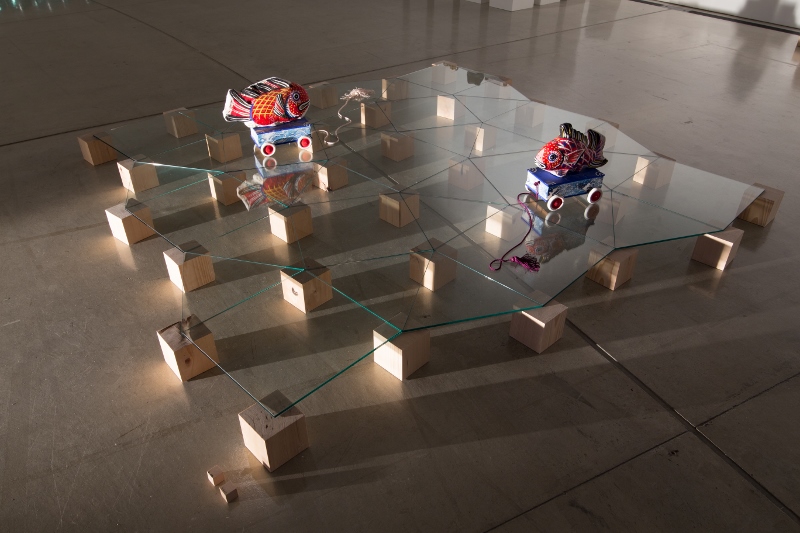

Left; BUILDVOID BIG Right; APPLE BOX STRUCTURE

Above; Bream Toy (Aomori City Archives) Below; GRLASS PEDESTAL Study

Front; 48 GLASS FLOAT

WHITE MAGNET 100

49 DRAWINGS

108 KOKESHIS (Kokeshi(Wooden dall), Aomori City Archives)

Kumapongome (TOKOLO Asao ×MATSUKAWA Shohei)

Gala Clockworks (Aomori), United Bows (TOKOLO Asao × IMAI Takeshi)

—

Related event “#1000 LIGHTs” September 11, 12, 2015

Photo by OYAMADA Kuniya

—

[Essay]

The Dynamic Equilibrium of Individual and Group

KANEKO Yukiko

Visiting Aomori Contemporary Arts Centre (ACAC) on a clear evening, guests will find the Exhibition Hall enveloped in the shadows of the trees cast by the setting sun. The shadows blend into a pattern, making it difficult to distinguish one type of tree from another. Together they form some kind of shape, covered in particles of transparent light. There is no way of knowing whether or not architect ANDO Tadao had envisioned such a sight when he designed the building, but the natural and fantastic patterns that appear on the building’s facade indicate that the architecture, while a foreign body, is a peculiar entity that is able to coexist in harmony with the forest.

The Jomon-period archaeological sites of Komakino and Sannai-Maruyama lie just a 20-minute drive away from the ACAC, and Heian-period ruins[1] can also be found in the nearby Nogi District. Aomori is also home to the culture of the Ainu, an indigenous people whose expansive territory also included Hokkaido and Sakhalin to the north. Far from the central areas of Japan, a distinctive Aomori culture has formed since its settlement by humans in the Jomon period.

Since 2013, the ACAC has hosted a series of annual winter exhibitions, curating and displaying properties of the Aomori City Archives. Artist Tokolo Asao joins the ACAC as the series’ fourth director, following previous programs by OH Haji, NAKAZAKI Tohru, and FUJII Hikaru.

The artists begin working in the spring and can spend anywhere between six months to a full year conducting research before the exhibition, which runs from February through March. Unique methodologies and approaches to production have been seen with each artist: Oh frequented the archives, diligently observing and deciphering items in the collection. Nakazaki, together with workshop participants, conducted hearings on his theme with residents of Aomori in preparation for the exhibition. Fujii consumed large volumes of literature regarding the history of modernization in Japan and in Aomori. This year, Tokolo travelled around the city in search of landscapes and architecture to observe and photograph. These works, collectively entitled 1000 PATTERNS AOMORI, document his travels and were displayed at the entrance to the exhibition.

From scenery to souvenirs, Tokolo captured the best of everything that he encountered on his road trip through Aomori in a square photography format to form a slideshow arranged in chronological order. Similar to how Charles and Ray Eames, in their film Powers of Ten, use a square frame to take the viewer on a journey that quickly spans both the furthest reaches of the galaxy and the subatomic world, Tokolo also uses his square format to freely zoom in and out on a variety of perspectives. Anyone can appreciate the new shapes seen as a result of the simple mechanism of changing perspective, even without a scientific understanding of the phenomena behind Powers of Ten. Similarly, 1000 PATTERNS AOMORI has a universal appeal, even without knowing what the photographs are of.

Rather, Tokolo deliberately strips the subjects in his frame of any narrative, allowing the viewer to fixate on the forms themselves.

From the entrance of the gallery, tools such as wooden sledges, various farming instruments, and spinning wheels are arranged in a line on the floor. Floor lights shine brightly across the arc-shaped gallery, bathing the artifacts in light and casting their shadows on the walls behind. Further into the gallery at the center of its arc, apple boxes are stacked to form Tokolo’s APPLE BOX STRUCTURE. The inside is filled with shishi-gashira lion heads, horse bells, an Ainu ikupasuy libation stick[2], anchors, and statues of Ebisu and Daikokuten. Light from a work lamp gives rise to shadows. In contrast to the spacious gallery outside, the inside of APPLE BOX STRUCTURE feels cramped, with barely enough room to fit just two people. Surrounded by numerous items from the archive, visitors are awestruck by the space’s overwhelming power yet calmed by its yellowish light and confined space, lulling them into the same comforting feeling of a Japanese shrine or temple.

The cultural artifacts within the Aomori City Archives are comprised of clothes and tools used in daily life. However, there was no single artist or ACAC curator who possessed a deep knowledge of folkloristics. Even without this knowledge, the very forms of the artifacts command great admiration. Tokolo used his ignorance of folklore to his advantage in this exhibition, focusing completely on the forms of the objects themselves, purging them entirely of any story or meaning.

Background context is lost among the shadows that the row of tools cast. These shadows are the purification and refinement of form. Philosopher and mingei folk-craft movement founder YANAGI Soetsu once said that a pattern is the portrayal of a blank mind, simplified and stripped away of nonessential properties.[3] One could say that Tokolo, in his exhibition, used refined forms to generate his monyo patterns.[4]

Past APPLE BOX STRUCTURE and deep inside the gallery, 25 statues of Daikoku, the god of wealth, sit 5 by 5 atop a 117mm square pedestal. Almost all of the cubic pedestals and short barriers that protect the items measure either 117mm or 105mm square. Additionally, an identification number was displayed on a 30mm cube for each work. As a rule, the cubes are used in the exhibition as a module, as they can be stacked and aligned. This is also the repetition of the square modules common to the photography format incorporated by 1000 PATTERNS AOMORI, the interlocking joint mat of BUILDVOID BIG, the construction paper and masking tape of used in BUILDVOID Study, the rows of glass sheets of GLASS PEDESTAL Study, and the 200mm frames used in 49 DRAWINGS, which showcased 49 of Tokolo’s previous works. Another closer look around the exhibition venue reveals the repetition of circles as well: in the archives’ spinning wheels and horse bells, shrine bells and glass fishing floats, and even in the heads of kokeshi dolls. Both the artworks that expand upon Tokolo’s kumapong series and Gala Clockworks (Aomori) also share these circular features. Moreover, individual items of the Aomori City Archives are yet another module: the 25 Daikoku statues, a wall covered in a 3×8 column of masks, and the huge number of ikupasuy libation sticks and shishi-gashira lion heads that line the APPLE BOX STRUCTURE.

Their repetition is linked to the increase and decrease of modules and accompanying variability in shape and size. It is no coincidence that so many of Tokolo’s artworks in this exhibition are variable in size and are videos that show the shapes of his monyo shift one after another. The variable nature of their size and propagation in the modules is a defining characteristic of Tokolo’s work. In the moment a module is repeated according to certain principles, the individual becomes part of a group, which then becomes a monyo. The patterns expand both horizontally and vertically as Tokolo successfully creates multi-dimensional works. Tokolo often uses the repetition of squares, equilateral triangles, circles, and other simple geometric shapes as modules in his work, but in this exhibition he interprets a variety of other mediums as modules, incorporating them into an experiment of creating patterns as a group, as previously mentioned.

At #1000 LIGHTs, a pre-opening event held in September 2015 in anticipation of the exhibition, Tokolo took circular candles and placed them inside disposable plastic cups and formed monyo by grouping them together. He created a module using their circular shapes together with the media of candles and cups.

Tokolo’s activities across a wide range of areas like architecture, product design, and fashion are a testament to his work: rather than call him transdisciplinary, it may be best to say that he is not confined to any one medium. To go one step further, his artwork may best be described as drifting without necessarily requiring a certain medium for its manifestation. In fact, the root of Tokolo’s expression lies more in the self-imposed rules of what to include in a module and how to form a group, than in the medium itself.

Just as the expressions of light and shadow change with every passing moment, Tokolo’s monyo suddenly change in shape and size in a matter of moments. They temporarily dwell within products or architecture, but eventually their vessels vanish over time.

His patterns then seek out another medium in which to manifest themselves. Time and again, patterns with no known creator have appeared in clothing, tools, architecture, and a whole host of other media, used by people since time immemorial. They acquire defining characteristics even as certain aspects change over time. Similarly, Tokolo monyo will undoubtedly become stronger, more intense, as they appear, disappear, and reappear in new and varied manifestations. In what forms and media will they appear in 100 or 200 years? Only time can tell.

[1] An Illustrated Guide to the History of Aomori and Higashi Tsugaru. (2007) Compiled by TAKIMOTO Hisafumi. Kyodo Publishing, Inc. p. 70.

[2] A spatula-like tool used in Ainu ceremonies.

[3] The Yanagi Soetsu Collection: An Advocacy of Buddhist Aesthetics. Yanagi Soetsu. Shoshi SHINSUI: 2012. p. 300.

[4] In describing his creations, Tokolo uses the more traditional word for patterns (monyo) rather than the more common, modern-day word (moyo). This demonstrates Tokolo’s subjective psychological distance from his subject. For example, if a great deal of stones were scattered on the ground, Tokolo may take a first look and describe them as a moyo, or pattern, in Japanese. However, after looking at them several times, he would deliberately start to use the word monyo to describe them instead.

Before beginning to work with patterns, Tokolo had produced logos before he started working with patterns. This relates to his idea that logos, when connected together, form monyo. The patterns in Tokolo’s works are collectively called monyo in this essay.

- 日時

- February 6 (sat) - March 13 (sun), 2016, 10:00~18:00

- 会場

- Gallery A

- 対象

- admission free